C.6 Historians of Eighteenth-Century Art and Architecture (HECAA) Open Panel

Thu Oct 21 / 9:00 – 10:30 PDT

voice_chat joinchair /

- Ersy Contogouris, Université de Montréal

HECAA works to stimulate, foster, and disseminate knowledge of all aspects of visual culture in the long eighteenth century. This open session welcomes papers that examine any aspect of art and visual culture from the 1680s to the 1830s. Special consideration will be given to proposals that demonstrate innovation in theoretical and/or methodological approaches.

Ersy Contogouris is Assistant Professor of Art History at the Université de Montréal. Her research focuses on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art, as well as on the history of caricature and graphic satire, which she studies through the lens of feminist and queer theories. She is interested in the history of the performance of the "statufied body" (attitudes, tableaux vivants, and others) from the eighteenth century to today. She is the author of Emma Hamilton and Late Eighteenth-Century European Art: Agency, Performance, and Representation (2018) and the guest co-editor, with Mélanie Boucher, of the issue Stay Still: Past, Present, and Practice of the Tableau Vivant published in RACAR (2019).

C.6.1 Collaging Colonialism: Mary Delany's Flora Delanica as Representation of Empire

Charles Reeve, OCAD University

Near the end of her long life — which included wealth inherited, lost and regained, writerly and artistic acumen and skilful politicking — Mary Delany veered down a new path. In 1772, she wrote her niece about inventing “a new way of imitating flowers”: she adapted the medium of paper mosaic, a popular pastime among middle-class women, to produce detailed floral representations. Thus began the Flora Delanica, comprising nearly 1,000 collages that Delany produced over the next decade — often using hundreds of papers, meticulously selected, trimmed and placed, to remarkable depictive and visual effect.

Although Delany called them “frippery,” these collages combined expertise in painting, decoupage and similar “womanly” arts with her passion for ideas, including Hannah More’s feminism and Carl Linnaeus’ classifications. Thus, the Flora overlaps with Delany’s other renowned project, similarly detailed and expansive: her Autobiography and Correspondence, published by Augusta Hall during the 1860s. Paradoxically, the expansiveness of these projects discourages explorations of their contextual embeddedness, the commentary on Delany merely reproducing her preference for description over analysis.

One thing overlooked by this approach — and this will be my talk’s focus — is how Delany’s Flora and life writing represent imperialism during the eighteenth century (that is, as imperialism reached its height, even while its unravelling commenced). In this context, and through the mediated form of collecting she performed by producing the Flora, Delany exemplifies what Jiang Hong recently identified as the “metropolitan” woman in relation to botany’s patriarchal and colonial practice: never travelling herself but diligently celebrating and consuming trophies of colonial botany in her domestic life. And, as we’ll see, while her Flora glided across colonialism’s surface, schematically representing British empire’s reach through the far-flung yet meticulously referenced origins of its specimens, her correspondence occasionally reveals more direct — if disconcertingly naïve — engagements with that ideology’s most rapacious forms.

Charles Reeve is an art historian at OCAD University, where he is chair of Liberal Studies. With Rachel Epp Buller, he is co-editor of Inappropriate Bodies: Art, Design and Maternity (Demeter, 2019). His next book, Artists' Autobiographies from Today to the Renaissance and Back Again, is forthcoming from Routledge. He is a past president of L'Association d'art des universités du Canada/Universities Art Association of Canada.

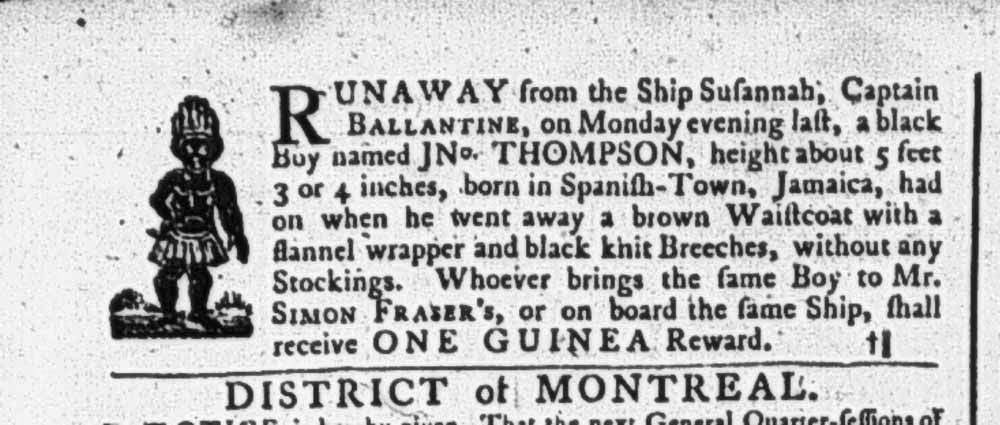

Fugitive slave advertisement from the Quebec Gazette (1779) with a cut depicting an enslavedperson using blended Indigenous-coded and African-coded stereotypical features. Digital image from Simon Fraser. “RUNAWAY from the Ship Susannah.” Quebec Gazette (Québec), no. 735 (30 September 1779), Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montréal.

C.6.2 Pictorial Depictions of Enslaved People in Quebec Gazette Advertisements, 1765–1794

Emily Davidson, NSCAD University

Newspaper printing in eighteenth-century Quebec was inextricably tied to the practice of slavery. The visual culture produced by the slave-owning publishers of the Quebec Gazette between 1765 and 1794 requires specific interrogation because, unlike most eighteenth-century slave advertisements in the British Atlantic, the pictorial depictions of enslaved people in this publication blended Indigenous-coded and African-coded stereotypical features. This study analyzes the possible meanings signified by the woodcut printing blocks which white Europeans created to represent enslaved people as hybridized and homogenized “others.”

I trace the historic development of this specific mode of representation within British print and advertising culture in both England and Virginia starting in the seventeenth century to reveal how these images were generated from an oppressive intercultural context. I discuss trends of woodcut use within the Quebec Gazette and comparative contemporaneous examples from newspaper publications in Georgia and South Carolina to show that this particular representation of enslaved people was not unique to Quebec publishing, although it was a substantially less common trend. Finally, I discuss what these images do and how they do it in order to connect this study to ongoing patterns of the misrepresentation of slavery within Canada and the ways visual culture acts to underscore historic and continued attempts by Euro-Canadians to control Black and Indigenous bodies (Charmaine A. Nelson).

Recent scholarship on fugitive slave advertisements that highlights the embodied nature of the textual descriptions of enslaved people (Nelson, Shane White and Graham White, David Waldstreicher) does not address the pictorial elements of these advertisements. The most comprehensive study of the visual culture of slavery in North America and Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Marcus Wood, Blind Memory) excludes Canada as a site of inquiry. This is the first study on woodcut blocks depicting enslaved people in slave advertisements published in Quebec.

Emily Davidson is a settler artist, activist, and graphic designer based in Kjipuktuk (Halifax, Nova Scotia). Her artistic practice uses printmaking to investigate the history of leftist political movements, imagine utopian futures, and agitate for social justice causes. Her current research focuses on the entangled relationship of print media in historic and ongoing colonization of Indigenous lands across Turtle Island and interrogates the role printers played in Transatlantic Slavery in the territories that became Canada. Emily graduated from NSCAD University in 2009 (BFA, Interdisciplinary) and is a current MFA candidate at NSCAD. Emily is a Research Assistant at The Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery. Emily is a recipient of the Canada Graduate Scholarships-Master’s Program in Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

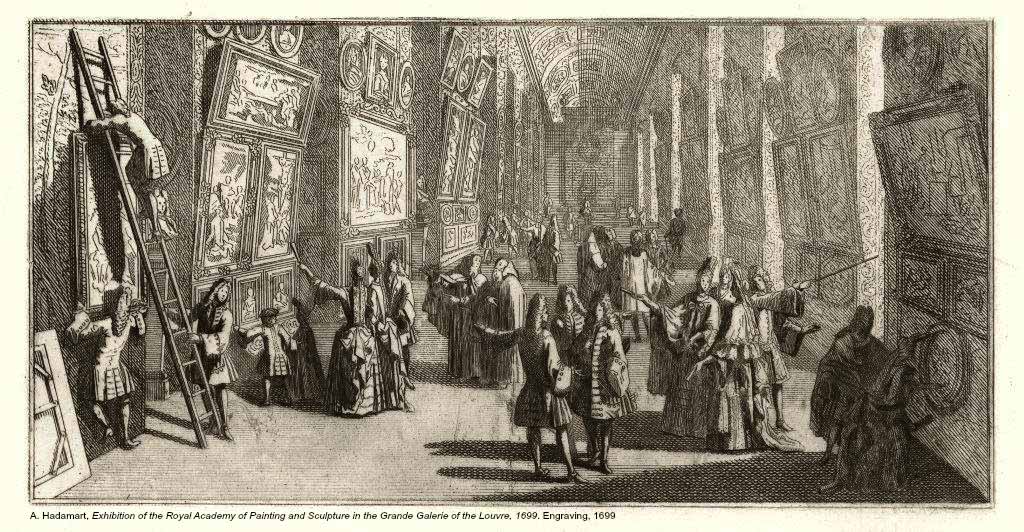

A. Hadamart, Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in the Grande Galerie of the Louvre, 1699. Engraving. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

C.6.3 Royal Spectacles and Social Networks: Salon Exhibition in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris

Mandy Paige-Lovingood, North Carolina State University

Following the Académie Royale's establishment of the Louvre Salon, scholars argue that salons were presented as major public events accessible to all classes of people. Thus, a lengthy struggle ensued between the Académie and critics over exhibition practices. Art historian Thomas Crow argues that the Académie's early salon exhibition was more pêle-mêle, failing to offer a coherent narrative to spectators, as it was arranged according to object size and shape. While this display has traditionally been judged as haphazard, simplistic, and lacking any inherent composition, when examined through the lens of the Académie, one finds that such a practice was a replication of their art genre hierarchy. As such, this paper reevaluates early salon exhibition practices in relation to the rules, regulations, and theories of the Académie to unpack display in early eighteenth-century Paris. Through an analysis of the salon exhibition practices of 1699 and 1704, I argue that the new "democratic" salon practices were not merely a hodge-podge display of objects. Rather, salon display remained couched within the crown's top-down approach by way of the Académie. Acting as a by-proxy of monarchical power, the Académie and its social network employed their hierarchical ranking system and art theory to counter critics and maintain their grip on regulating aesthetics by promoting an absolutist gaze. Such a mode of viewership, which was dictated by the ancien régime monarchy, the Académie's most important patron, acted as a tool for maintaining and bolstering their prestige and noble taste to the public, rather than as a means for socialization and elevating public taste, as previously suggested. Thus, this reinterpretation situates a coded salon spatial arrangement almost forty years earlier than previous scholarship and opens the door for recognizing the power structures embedded within the display and the many ways in which it functioned.

Mandy Paige-Lovingood is a Public History doctoral student at North Carolina State University (NCSU) specializing in the interpretation of eighteenth-century cross-cultural connections between the Ottoman Empire and France. Prior to attending NCSU, Mandy received her MA in Art History under the guidance of Dr. Mary Sheriff and Dr. Melissa Hyde at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Her primary area of interest examines the intersections taking place in turqueries between gender, identity, and exhibition and examines how they convey social, political, economic, and gendered meanings in the private and public spaces of the past and present.

Church or Chapel of Nossa Senhora [Our Lady] das Salvas, Sines, Setúbal, Portugal. Photography by Madalena Costa Lima.

C.6.4 Neo-Gothic or Gothic Revival? Attitudes toward Late Medieval Architecture in the Eighteenth-Century: The Portuguese Case

Madalena Costa Lima, University of Lisbon

Despised during the early modern period, medieval architecture reached the eighteenth century poorly known and barely studied, as all art forms of the same period did. As such, constructions and artistic productions from back then were indistinctly referred to as "gothic," a word mostly used as an adjective and with a strong derogatory significance.

It was precisely during the eighteenth century that medieval architecture, specifically late medieval architecture, which we now designate as Gothic, became the subject of a more attentive examination and increasingly an object of study and interest. Great Britain led the way, with Christopher Wren and a few others, drawing attention to gothic buildings and their particularities. By the turn of the century, however, gothic architecture was an architectural or a cultural theme, generally present in Europe, namely in Portugal, the continent’s westernmost kingdom. In England, the enthusiasm of a certain elite towards the medieval imaginary originated a specific type of poetry and literature, which accompanied and stimulated the interest for the architecture and art of that same period, leading historians, such as Kenneth Clark, to claim the existence of a cultural movement designated "Gothic Revival." In the Portuguese context, where the cultural background is so different, is it still proper to designate the gothic architectural interventions made in the eighteenth century as "Gothic Revival"? What could, then, have motivated these "neo-gothic" constructions?

I propose to consider these questions, stressing the cultural and aesthetic fundamentals of the architectural interventions in gothic in the Portuguese eighteenth-century, addressing its coexistence with the Baroque, Rococo and Classical styles, and most of all, underlying the emergence of the notion of "historical heritage" in Portugal, as in Europe.

Madalena Costa Lima completed her PhD in History, specialized in History of Art and Heritage, at the University of Lisbon (UL), in 2014, with a dissertation on architectural heritage in Portugal during the eighteenth and early-nineteenth century, awarded with a PhD fellowship from the Portuguese foundation "Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia" (FCT). She gave lectures on Heritage History and Architectural History at the UL. She gives talks and writes articles on these topics and on the history and culture of the long eighteenth century. She is a researcher at CLEPUL (Research Centre on Culture, History, and Literature) and ARTIS (Institute of Art History), research units of the School of Arts and Humanities of the UL. She is currently involved in the project POMBALIA: The Historiographical Writings of the Marquis the Pombal, founded by the FCT.