E.3 Sites of Photographic Knowledge: Studios and Networks, Part 1

Fri Oct 22 / 9:00 – 10:30 PDT

voice_chat joinchairs /

- Martha Langford, Concordia University

- Eduardo Ralickas, Université du Québec à Montréal

This two-part session aims to foster interdisciplinary dialogue between scholars in all fields working on the historical and contemporary problem of photographic knowledge. We have sought proposals stemming from the history of photography, art history, the visual arts, sociology, aesthetics, anthropology, visual studies, cultural studies, and communications, or somewhere in between. Our focus has been on two sites of photographic knowledge, namely, studios, and networks.

Spaces of creation, the studio and researcher's cabinet/study, are increasingly present in exhibitions and publications, as both scholars and publics become curious about the life of the mind and the material culture behind the scenes. The studio is a space of situated and socializing knowledge, offering both intimacy and exposure to works-in-progress. In the vein of "exploding cinema," we are interested in the "atelier éclaté," but we are also looking at the photographic historian's spaces of communication — the book, the slide lecture, the conference, etc. — as "epistemological studios."

Network thinking has been reshaping art and photography history through biographical methods ("object-lives") and institutional recasting in terms of national and global circulation. Under current conditions of impactful social networking, we are particularly interested in relational studies of reality effects and photographic truth claims. The session, therefore, considers projects that have brought studios and/or networks to life, and particularly those that complicate current methodologies or ways of thinking about photography's epistemic privilege.

Martha Langford is a Distinguished University Research Professor of Art History at Concordia University and Research Chair and Director of the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art. She participated in the four-year team-research project Networked Art Histories, led by Johanne Sloan. Langford is the principal investigator in the interuniversity research group Formes actuelles de l'expérience photographique (FAEP) : épistémologies, pratiques, histoires whose activities have included two spring schools, five UAAC sessions, and a book series in collaboration with Artexte.

Eduardo Ralickas is a Professor of Art History and Aesthetics at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM). He obtained his PhD at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) and the Université de Montréal. He also holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Concordia University, where he majored in photography while studying mathematics, philosophy, and art history. Before joining UQAM's Department of Art History, he taught courses in art theory, including the theory and history of photography at Concordia University and the Université de Montréal. He is a founding member of FAEP. Recent papers include L'atelier comme méthode. Le cas de Raymonde April.

E.3.1 Virtual Communication within Socio-Technical Networks: Postal Photographic Clubs in Britain, 1880s–1910s

Sara Dominici, University of Westminster

The launch of the Royal Mail's parcel post service in 1883 coincided with the increase of amateur photographers in Britain, supporting new ways for these practitioners to come together: the postal photographic clubs, small groups of self-organized photographers that circulated a portfolio of prints and texts among themselves for mutual criticism. This paper considers the influence that the infrastructure of the postal system had on photographers' opportunities for sociability, self-expression, and learning in Britain from the early 1880s to the early 1910s, by which time postal photographic clubs had become almost ubiquitous. It focuses, in particular, on the role played by the collaborative nature of postal photographic clubs in the production of photographic knowledge.

I will explore this topic by looking at three interrelated elements. First, the role that the parcel post, a modern technology of both communication and transport, played in the emergence of postal clubs by facilitating the virtual mobility of photographers. Second, how postal communication took place through distinct spatio-temporal and material experiences that enabled photographers to contribute actively to the form and content of communication, in doing so becoming part of a modern network. Third, how this impacted on the social interaction between photographers in a way that transformed the perception of each member's individual role in the production of photographic meanings and values.

Sara Dominici / I am a Senior Lecturer and the Course Leader for the MA Art and Visual Culture at the University of Westminster, London (UK). My current research studies the wide range of photographic practices that shaped people's experience of their world in Britain between the 1870s and the 1930s, focusing in particular on the significance of the technical and socio-cultural interrelations between photography and other media and technologies (i.e., photographic press, personal transport technologies, postal system, darkroom technologies). In this work, I consider the materiality of photographic experiences in their interaction with other tools, and not the visual product alone, as constituting photography's cultural significance. I am the author of Travel Marketing and Popular Photography in Britain, 1888–1939: Reading the Travel Image (Routledge, 2018), and I have published in titles including History of Photography, Image [&] Narrative, photographies, Photography and Culture, Science Museum Group Journal, Source, The PhotoHistorian, and Trigger.

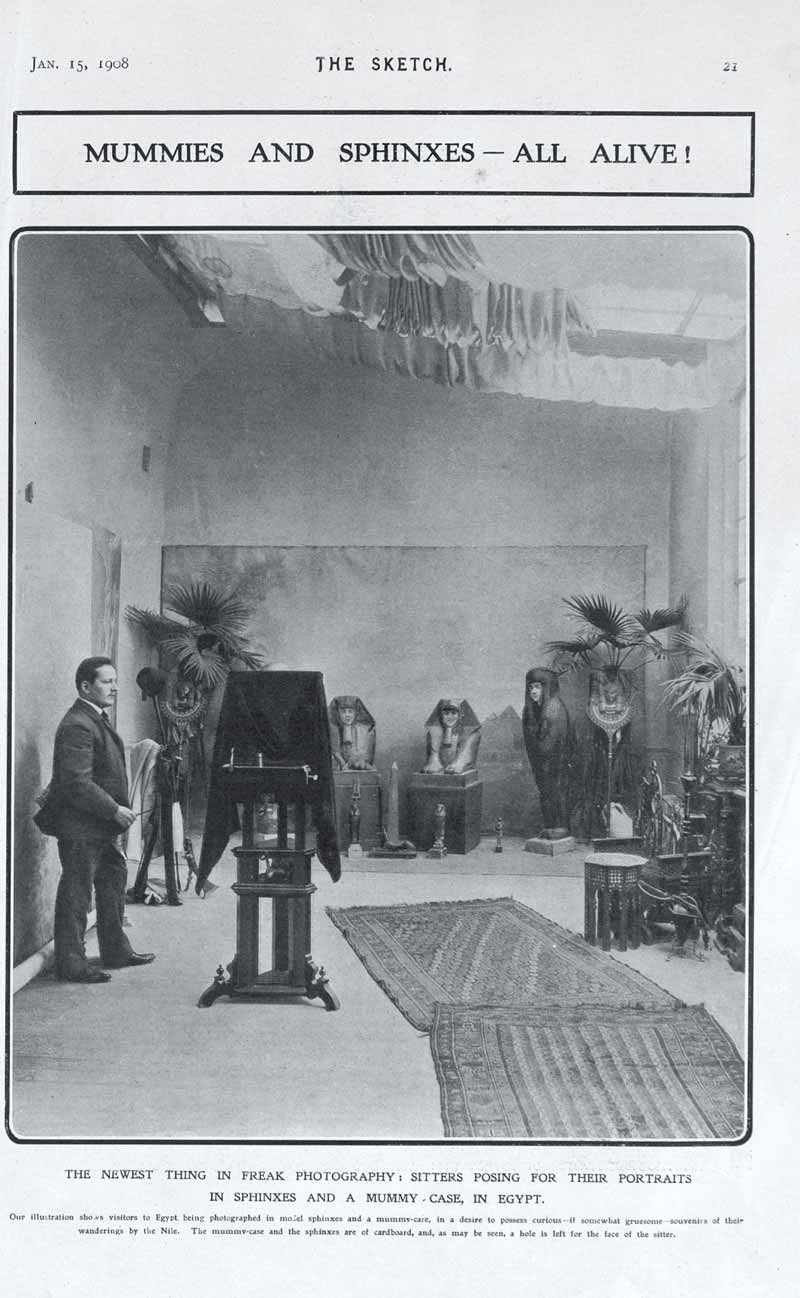

Mummies and Sphinxes—All Alive! The Sketch 61, no 781 (15 January 1908): 21.

E.3.2 Me as a Mummy: Portrait Studios and Performative Egyptomania

Stéphanie Hornstein, Concordia University

In October 1898, the Kalamazoo Gazette ran a short, but spirited, column on the latest trend in "Mummy Pictures." It announced the fashionable practice of having one's portrait taken while peering out from an Egyptian sarcophagus. This fad, which successfully tapped into a generalized Western obsession with pharaonic history, had apparently originated in Cairo's photography studios, but was rapidly spreading to New York and Paris. Judging by the portraits of Katharina Schratt and Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who both had their likeness captured as living mummies, it also seems to have been popular with the Austrian monarchical elite. Though press coverage of "the newest thing in freak photography," as another weekly termed it, would chatter on as late as 1912, there are surprisingly few surviving images that attest to what must have been a lucrative side venture for commercial photographers in Egypt and elsewhere.

Informed by sociologist Erving Goffman's theories, this paper investigates mummy portraits as earnest, if carnivalesque, presentations of self that were facilitated by the performative space of the portrait studio. While a common desire to show oneself as worldly can be discerned, the focus here is not only what motivated sitters, but how photographers fostered these experiences. Under what circumstances would such photographs, which very literally invited patrons to step into their Orientalist fantasies, have been produced? How did they circulate, and who were their intended audiences? To answer these questions, cabinet cards and primary texts are brought forward as clues to the widespread and accepted practice of cultural cross-dressing, of which mummy portraits were an atypical sub-genre. A particular emphasis is placed on the Strommeyer & Heymann studio, which appears to have been trendsetters in this domain. Finally, links to the macabre tourist trade in Egyptian mummies and turn-of-the-century body politics are explored.

Stéphanie Hornstein is a PhD candidate and course instructor in the Department of Art History at Concordia University in Montreal. Her doctoral research is concerned with tracing patterns in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century travel photographs of the broad region that was designated by Westerners as "the Orient." Her writing can be found in Ciel variable, History of Photography, RACAR, and Counterpoint.

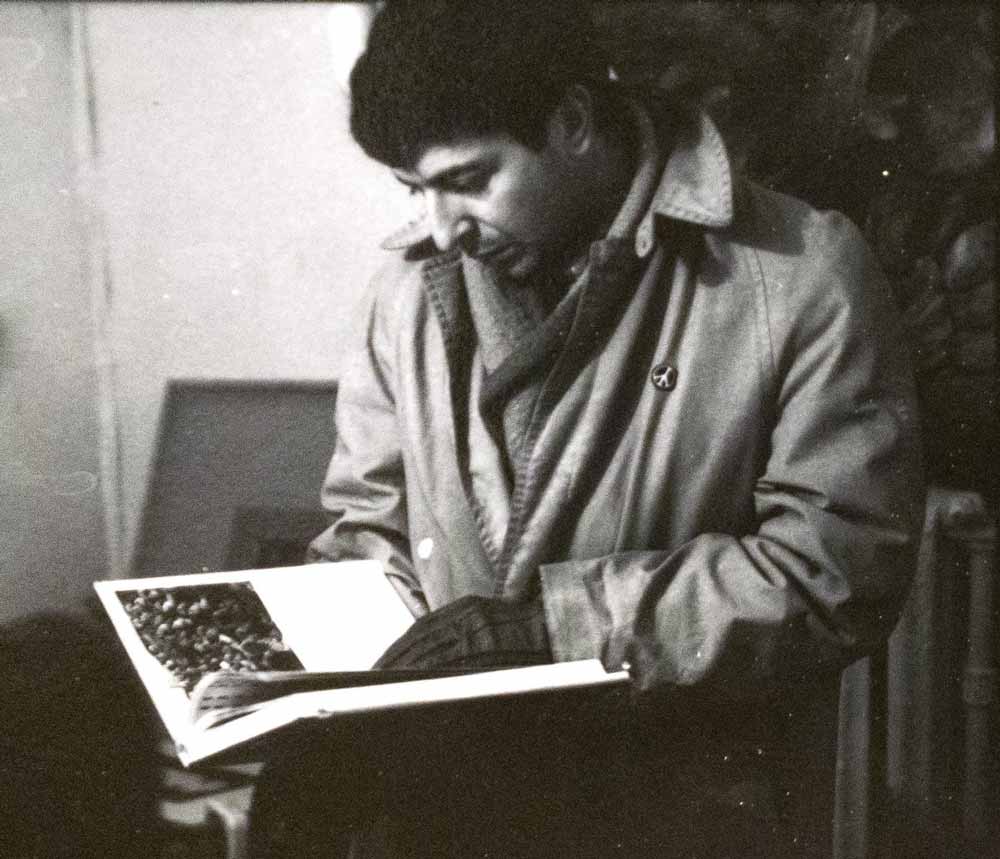

John Max, Leonard Cohen peacefully reading a photobook at John Max’s house, 1961. © The Estate of John Max, Courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery.

E.3.3 Leonard Cohen, Robert Hershorn, and Alanis Obomsawin walk into a house…

Michel Hardy-Vallée, Independent Scholar

The house is that of photographer John Max, and they are here to look at his photographic prints and books on a Sunday, 19 March 1961, while their portraits are being casually snapped. Max's resulting images of the poet, the businessman, and the filmmaker have neither been published nor exhibited during his lifetime, as with countless other projects. However, the mise en abyme of the medium in these images point today at a larger question: what did it mean to care about photography in early 1960s Montréal?

At the end of the decade, Lorraine Monk would declare this era a "photographic wasteland." Although scholars have since stressed the role of photo reportage in the illustrated press, the booming vernacular market, and the continuing tradition of fine art photo clubs, there remains the impression of photography not being a centre of attention and debate before the arrival of the National Film Board and the National Gallery of Canada.

Max's images, as well as his own trajectory, are rich with evidence to the contrary and offer inroads to a better understanding of early 1960s photographic culture in the country. Key to his self-understanding is the myth of bohemia. Intersecting geography, demography, social stratification, ethos, fame, and the notion of cultural progress, « La bohème » was a pre-existing discourse that accompanied prospectively and retrospectively the trajectory of artists in Montréal. It constituted a network both real and imaginary, linking people and representations across time and spaces.

Reading Max's practice of the early 1960s against the discourse of bohemia, I show how it legitimized photography as the antechamber of fame, necessitating its own kind of visual literacy, while the performative identity of bohemia offered opportunities to cultivate an intimate, diaristic and subjective approach to photography that is still today the vernacular of social media.

Michel Hardy-Vallée holds a PhD in art history from Concordia University in Montréal. His main research interests include the history of Canadian photography in the twentieth century, the photographic book, visual narration, interdisciplinary artistic practices, aesthetics, and the archive. He has advised on photographic prints acquisitions by museums and private collections and has taught the history of photography. He is currently adapting his doctoral dissertation about Canadian photographer John Max into a monograph and has contributed numerous book chapters on photographic narrative and graphic novels. His most recent article is "The Photobook as Variant: Exhibiting, Projecting, and Publishing John Max's Open Passport" in History of Photography (43:4, 2019).