A.4. Arts, Social Action and Quiet Resistance: What Counts as Activism? Part 1

Thu Oct 15 / 9:00 – 10:30

voice_chat expiredchair / Rébecca Bourgault, Boston University

In a discussion on protest art, art historian Tunali (2017) points to the persistent tension between political activism and artistic representation, where the:

“aestheticization of politics leads to the spectacularization of art to make political ideologies attractive, [and] the politicization of aesthetics strips art of its autonomy, thus its power to operate as a creative process” (67).

The panel invites submissions of artistic and scholarly works that interrogate the activist goals and approaches of protest art, socially engaged practices, absence as gesture of dissent, quiet activism, and/or DIY as creative resistance, welcoming a wide range of theoretical and artistic perspectives. Debates could include the controversial responses to the term BIPOC by those it seeks to collectively identify, as well as insights from art/environmental activism often negotiated by groups that use grassroot and place-specific methods of resistance. All formats of presentations are welcome.

Reference: Tunali, T. (2017). The paradoxical engagement of contemporary art with activism and protest. C.Bonham-Carter, N. Mann (Eds.). Rhetoric, social value and the arts, pp. 67-81. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: 10.1007 /978-3-319-45297-5_5

Rébecca Bourgault is a visual artist and an interdisciplinary scholar and educator. An assistant professor at the School of Visual Arts, Boston University, she holds an Ed.D from Teachers College, Columbia University, NYC, an MFA from the University of Calgary, and a BFA from Concordia University, Montreal. Her research has been presented and published in visual and written forms in North America and abroad. Current research interests include socially engaged art practices and arts-based research methods and pedagogies. She lives and works in Massachusetts.

Photo: Julie Hollenbach.

A.4.1 Whose Personal is Political? Troubling Privileged Affect in White Feminist Craftivism

Julie Hollenbach, NSCAD University

This paper presents an intersectional feminist analysis of craftivism; the social movement where dissent is expressed through crafty forms of activism by individuals and collectives alike. Through examining craftivism, my paper considers how amateur crafting practices are tied fundamentally to the maker’s sense of self, and how that self is connected to local and global social formations and circumstances. Furthermore, as craftivist culture leans heavily into gendered ideologies of labour and material, my paper assesses amateur textile’s bourgeois and feminine associations with the soft, the gentle, and the domestic, and how these associations strongly impact craftivism’s mobilization as a non-violent form of protest. Craftivism’s emphasis on either a traditional femininity or an uncritical essentialist feminism reproduces many of the pitfalls that faced women’s rights activists in the 1970s. Where white feminists aimed to disrupt the patriarchal hegemony and claim public space by demanding that their ‘personal is political,’ Black women and women of Colour have always occupied the public sphere through labour and have had their voices, their feelings, and their bodies forcibly policed or erased. Craftivism seems to be limited not only to the people who have the resources (time and money) to craft, but the luxury to express their dissent publicly in a gentle, non-violent manner. For many people – racialized, disabled, and poor people especially, and often through the intersections of oppression, queer and transgender people – protest is dangerous because it presses on their lives through the reality of systemic oppression which is insidiously and brutally violent. A call for craftivism to become more intersectional and reflexive in its analyses and application is beginning to take hold, though it remains to be seen whether craftivism will shift to respond to these challenges, or stagnate and give way to a different form of radicalized expression mobilized through textiles and craft.

Julie Hollenbach is assistant professor of craft history and material culture at NSCAD University (K’jipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia). Julie received her PhD from Queen’s University in Art History for her research on craft as a social practice. Her ongoing research addresses craft practices and craft cultures at the intersections of history and location, tradition and ritual, contact and connection, meaning and use.

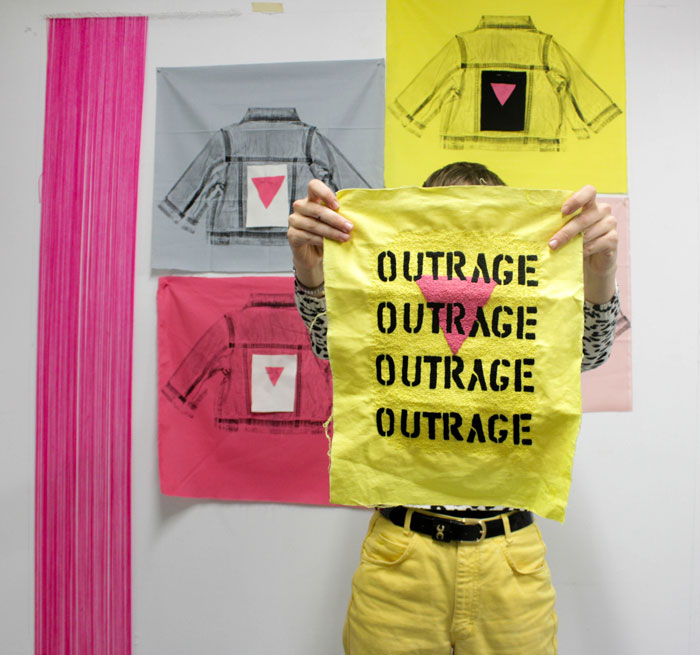

Emily Davidson with works in progress for her presentation Towards Queer Futures: Making Art with Activist Archives.

A.4.2 Towards Queer Futures: Making Art with Activist Archives

Emily Davidson, NSCAD University

I will present a body of artwork currently under development in which I engage political imagination by reapproaching queer resistance images through embroidery and quilting. These artworks are connected to a body of research guided by the questions: Are there practices that participate in the formation of queer futures and what characterizes these practices? Moreover, can these practices resist cooption by neoliberal colonial capitalism? My artworks aim to investigate fault lines in neoliberal colonial capitalism and activate any potential energy left by traces of past activism at these fault lines. Specifically, I investigate and redeploy protest imagery and activist graphic design from North American gay and lesbian social movements during the Western AIDS epidemic prior to 1996. In doing so I explore the archival turn (Kate Eichhorn) in activism and interrogate how archives and artistic institutions such as museums, galleries and universities limit and order radical queer materials. The work queers and complicates protest art by mixing images from the past and present which are variously activist, archival, pop-culture, personal, symbolic, and abstract. I aim reveal some of the ways queer futures are formed and to provide glimpses of possibilities for how activist and artistic processes might resist cooption by neoliberal colonial capitalism.

Emily Davidson is a settler artist, activist and graphic designer based in K’jipuktuk (Halifax, Nova Scotia). Her artistic practice uses printmaking to investigate the history of leftist political movements, imagine utopian futures, and agitate for social justice causes. Emily graduated from NSCAD University in 2009 (BFA, Interdisciplinary) and is a current MFA candidate at NSCAD. Emily is a recipient of the Canada Graduate Scholarships-Master’s Program in Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

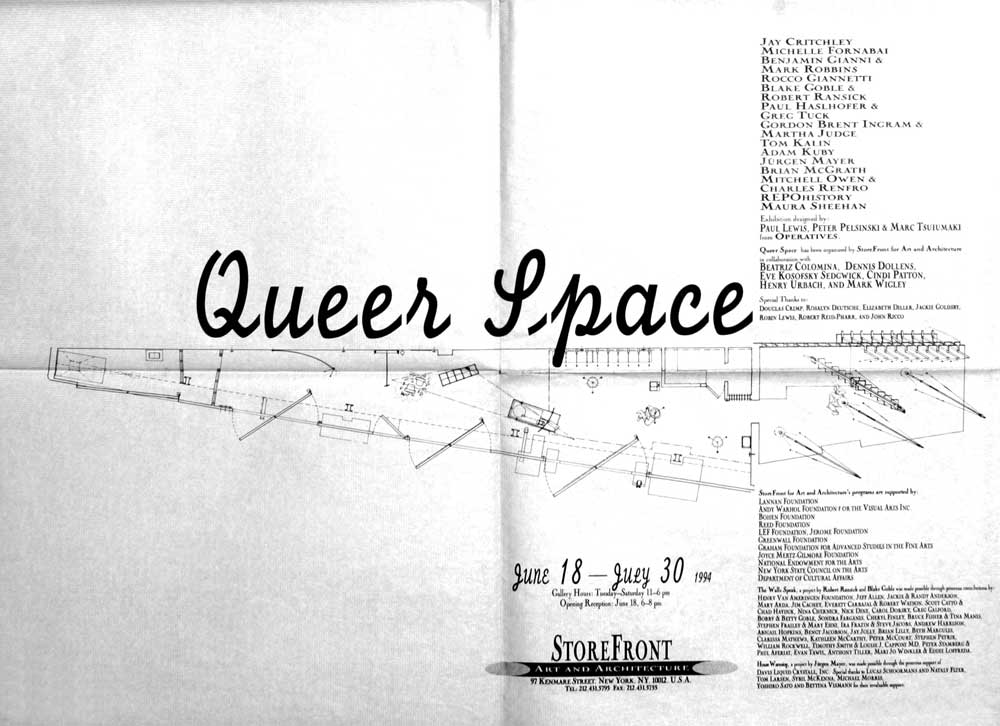

Queer Space exhibition poster/catalogue, Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, 1994 (Credit: Storefront for Art and Architecture)

A.4.3 Queering Space? Tensions between Ethics and Aesthetics in Activist Approaches to Design

Olivier Vallerand, Arizona State University

Definitions of “queer” vary greatly, from activist to theoretical to mainstream discourses. In turn, architectural theorists, historians, and practitioners have used “queer space” to discuss both political challenges to architectural education and disciplinary knowledge and aesthetic challenges to formal conventions. Through an analysis of essays, exhibitions, and performances, this paper explores how queer space thinking in architectural discourse has developed following different ethical or aesthetical objectives since its emergence in the 1980s.

Early queer space thinkers such as John Paul Ricco, Henry Urbach and Aaron Betsky explicitly contrasted the objectives of their approaches. Similarly, the Storefront “Queer Space” exhibition (1994) deliberately asked its participants to address how they defined queer space, exploring as much the use of public space by gay and lesbian people than the creation of safer domestic space. In parallel, the Organization of Lesbian and Gay Architects and Designers and other groups were both fighting for better visibility and representation and supporting victims of the AIDS pandemic. More recently, practitioners such as MYCKET have explored the productive tensions in thinking about queerness as a project of either aesthetic or ethic.

The paper thus focuses on untangling how architects and designers link queer political activism and queer theory, highlighting, challenging or reinforcing the difficult relation between formal and social critiques. Building on the idea that challenges to traditional forms of designing or writing highlight the social normativity of those forms, many have sought to propose new ways of thinking about how one experiences space. Through a comparison with how feminist and race scholars have approached similar tensions, I argue for a renewed focus on identifying how queer space activists have explicitly framed their objectives – or avoided to do so – to productively understand the limits and successes of queer approaches.

Olivier Vallerand is a community activist, architect, historian, and assistant professor at The Design School at Arizona State University. He completed a PhD in Architecture from McGill University and post-doctoral research at UC Berkeley. His research focuses on self-identifications and their relation to the use and design of the built environment, on queer and feminist approaches to design education, and on alternative practices of architecture and design. His book Unplanned Visitors: Queering the Ethics and Aesthetics of Domestic Space (2020) discusses the emergence of queer theory in architectural discourse. His research has been published in the Journal of Architectural Education, Interiors: Design | Architecture | Culture, Inter art actuel, The Educational Forum, The Plan, Captures, and in the edited volumes Sexuality (Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art) and Making Men, Making History: Canadian Masculinities across Time and Place. He also regularly writes for Canadian Architect.