B.4 Arts, Social Action and Quiet Resistance: What Counts as Activism? Part 2

Thu Oct 15 / 11:00 – 12:30

voice_chat expiredchair / Rébecca Bourgault, Boston University

In a discussion on protest art, art historian Tunali (2017) points to the persistent tension between political activism and artistic representation, where the:

“aestheticization of politics leads to the spectacularization of art to make political ideologies attractive, [and] the politicization of aesthetics strips art of its autonomy, thus its power to operate as a creative process” (67).

The panel invites submissions of artistic and scholarly works that interrogate the activist goals and approaches of protest art, socially engaged practices, absence as gesture of dissent, quiet activism, and/or DIY as creative resistance, welcoming a wide range of theoretical and artistic perspectives. Debates could include the controversial responses to the term BIPOC by those it seeks to collectively identify, as well as insights from art/environmental activism often negotiated by groups that use grassroot and place-specific methods of resistance. All formats of presentations are welcome.

Reference: Tunali, T. (2017). The paradoxical engagement of contemporary art with activism and protest. C.Bonham-Carter, N. Mann (Eds.). Rhetoric, social value and the arts, pp. 67-81. Palgrave Macmillan. DOI: 10.1007 /978-3-319-45297-5_5

Rébecca Bourgault is a visual artist and an interdisciplinary scholar and educator. An assistant professor at the School of Visual Arts, Boston University, she holds an Ed.D from Teachers College, Columbia University, NYC, an MFA from the University of Calgary, and a BFA from Concordia University, Montreal. Her research has been presented and published in visual and written forms in North America and abroad. Current research interests include socially engaged art practices and arts-based research methods and pedagogies. She lives and works in Massachusetts.

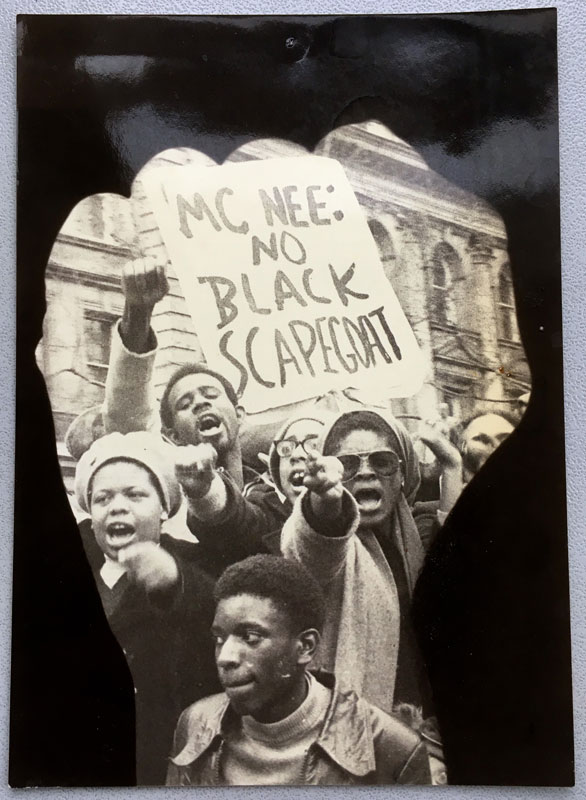

Author and caption unknown (c) George Padmore.

B.4.1 A Typology of ‘Direct Action Photography’: On the Merger of Political Activism’s Lexicon and the Photographic Vocabulary (1958-89/Britain)

Taous R. Dahmani, Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne & Maison Française d’Oxford (CNRS University of Oxford)

This paper does not aspire to discuss the possible ruptures between political and artistic facts but wishes to analyse the moments when uprisings and the art world meet, dialogue and debate. It pursues the cyclical interactions between these two spaces. However, against the grain of the widespread question: how artists might have an actual political effect on the real world, I would rather address the subject of how the real world impacts artistic creation and the art world ecosystem (museum, galleries, exhibitions, publications, etc.).

Successively, throughout history, social occurrences have run into and adhered to art moments – or art movements. In this paper, I would like to explore this question through the historical lens of racial minorities’ struggles for rights and freedoms and their little-known embodiment in British history. I would also like to focus on the photographic medium and its trajectory from printed matter to its reutilisation and appropriation by artists in the 1980s, as well as their awareness that the representation of revendications was not enough and that change needed to happen within the art world too. North American art history has demonstrated the multiple links between the Civil Rights Movement and artistic creation, however research on the subject is still quite scarce in other geographical areas such as England. The photographic representation of postcolonial migrants as actors of their civic and political journey; then as the subject of a large iconography of demonstrations, protests and uprisings and finally as authors of photo-based creations anchoring their political commitments in the image is at the heart of my endeavor here. As such, for this paper, I propose considering the different levels of photography as "direct action" in the socio-political context of England (culminating with the two Thatcher governments) and within the frame of the "politics of representation."

Following the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 in Minneapolis (USA), and at the time of writing this proposal, I, once again, find the enactment of this 'logical sequence' of events: first a succession of amateur or journalistic images representing an act of violence, then an extension through amateur or journalistic images of demonstrations and uprisings, then repercussions in artistic thought and contemporary creation, and finally a more or less important incidence within artistic institutions, forced to echo the rumors of the streets within the physical and ideological walls of the white cube. By means of examples from the late 1950s to the late 1980s, our typology makes it possible to follow the path of the recurring narrative arc of systemic racism from the streets to the art institutions via the artists, and as such, help understand its contemporary resurgences.

Taous R. Dahmani is a PhD candidate in the History of Art Department at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. She is doing a thesis in history of photography under the supervision of Prof. Michel Poivert and taught the history of 20th century photography for three years. She is the recipient of the Prix de la Chancellerie and is currently based in Oxford at the Maison Française (CNRS). Her thesis is entitled: Direct Action Photography: a typography of the photographic representation of struggles and the struggle for photographic representations (London, 1958-1989). In November 2018, she published an article entitled « Bharti Parmar’s “True Stories”: Against the grain of Sir Benjamin Stone’s photographic collection », in PhotoResearcher (no°30). Her chapter on Polareyes, a 1987 Black British female photographic journal is forthcoming in Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States in the Long 1980s, SUNY (2021). In October 2020, as part of the Photo Oxford Festival, in collaboration with the Bodleian Libraries, she is organizing a conference entitled Let Us Now Praise Famous Women: women’s labour to uncover the works of female photographers.

B.4.2 Agnostic Possibilities in Ontario’s Regional Galleries, A Proposition

Emily Cadotte, Independent

This paper evaluates the relevance of the regional public art institution in Ontario as it relates to the contemporary global populist moment. Communities in sparsely populated regions are frequently less exposed to cultural, racial, and class differences, making them potentially more susceptible to the rhetoric of right-wing populism. The regional gallery has an opportunity to introduce affective and agonistic presentations of difference that question and complicate existing hegemonic forces. Drawing on theories of public space from Rosalyn Deutsch, antagonism in relational practice from Claire Bishop, and the educational turn from Janna Graham, this paper finds that public art galleries have the capacity to produce agonistic civic spaces. These agonistic tensions, as articulated by political theorist Chantal Mouffe, put into question current hegemonic forms, encouraging the formation of new counter-subjectivities among audiences. These findings are supported by two case studies: Peterborough’s artist-run centre, Artspace, and Oshawa’s Robert McLaughlin Gallery. Interviews were conducted with the curators of each institution, and several exhibitions and programs were analyzed based on the merits of their agonistic potential.

Emily Cadotte has worked as an arts administrator at c magazine, Blackwood Gallery, and the Thames Art Gallery. She holds an MA at OCAD U where she was awarded the program medal for Contemporary Art, Design and New Media Histories (CADN) and completed her BFA at Concordia University. She has presented at conferences at OCAD U and published in Canadian Art Magazine and the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK).

B.4.3 Art History and ‘a’narchism

Emily Dickson, Western University

Books penned by Marxist art historians weigh down bookshelves everywhere, and yet anarchist art historians are practically unheard of. While some scholars have attempted to write anarchist art histories of the twentieth century, such texts frequently end up looking more like a hodgepodge of artists who have never expressed anti-authoritarian sentiment, rather than taking anarchism as a political philosophy, and as a framework for art historical methodology, seriously. What does it mean to think art history anarchistically? This is one of the questions that my research for the last few years has explored. Thinking art history anarchistically has a number of critical implications: not just for the subject or discipline of art history itself, but also for the objects of our study. When we live in a time where increasingly political action is manifest anarchistic form, and as politically engaged art practice expands, our art historical tools must also. This presentation an art historical approach to art history can mean, drawing on my own research into bureaucracy as an example, and through the cases of artists Francheska Alcantara, and Ravio Puusemp.

Emily Dickson is a writer and art historian presently engaged in a Doctoral Candidacy at Western University. Her research investigates art and bureaucracy, art in the public realm, and the intersections of art and anarchist politics and political philosophy.