chairs /

- Oluwasayo Taiwo Olowo-Ake, University of British Columbia

- T’ai Smith, University of British Columbia

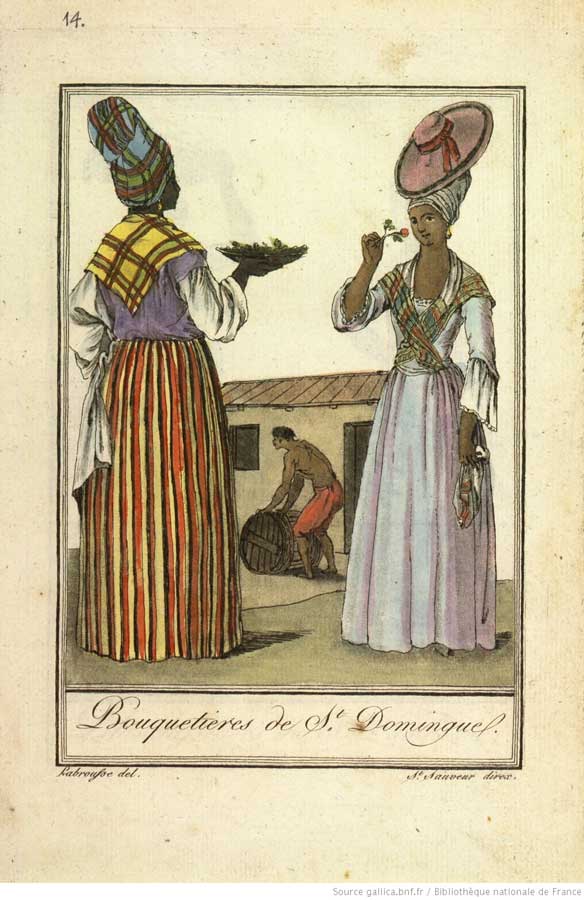

Redressing a blind spot from last year’s panel “The Art of Camouflage,” we aim to tackle this theme again through the lens of race. Nearly 70 years after the publication of Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952), the experience of racial profiling that Fanon described is increasingly visible to a global audience, through videos published on the news and social media platforms. Recognizing the contradictory everyday experience of race for people of colour — realities that are both immediately perceptible and too frequently overlooked, this panel will interrogate the visibilities and invisibilities of racial violence from a global and trans-historical perspective. We ask: How can art and design practices address a world governed by both overt and masked racial biases? Is the protection offered by camouflage in virtual and real spaces an artifact of white privilege? Can camouflage be used strategically to counter racial violence, or could it be part of the problem?

Oluwasayo Taiwo Olowo-Ake is a graduate student in critical curatorial studies at the University of British Columbia. Her research focuses on retelling the stories of Yoruba Nigerian artworks in Western collections

T’ai Smith is associate professor of modern and contemporary art history at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Author of Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design (University of Minnesota Press, 2014), she has lectured and published internationally on textile media and design in modern art and theory. She is currently working on two book manuscripts: Fashion After Capital and Textile Media: Tangents from Modern to Contemporary Art.

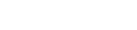

Labrousse (drawing) and Laroque (etching). Bouquetieres de Saint-Domingue, 1796. In Jacques Grasset-Saint-Sauveur’s book, Encyclopédie des voyages (1796) Intaglio (Colour engraving). 24.8cm

B.7.1 ‘A Dark Cotton Cap with Yellow Strings’: Sartorial Trends in the French Empire

Joana Joachim, McGill University

Black women’s hair and dress during the 17th and 18th centuries were a source of intense discomfort for the white ruling class as it existed against the backdrop of racial mixing and white men’s attraction to them. As a result, Black women in this period were forced to hide their hair through sumptuary laws such as the tignon edict. At the same time as the tignon, a type of head wrap, served to make hypervisible their Blackness and therefore signal their forced “inferiority”, Black women used this item of dress as a site through which to resist subjugation through fashion. In reflecting on the implications of hair and dress as sites of resistance within the framework of self-preservation and self-care, I locate them in the crossover between the Hortense Spillers’ concept of “body as flesh” and Mercer’s comments regarding Black cultural production as a series of solutions emerging from socio-political problems. In keeping with Steeve O. Buckridge’s claim that “sumptuary laws existed in many societies, primarily to preserve class distinction”, I unpack the effect of these laws on Black women in the French Empire (Buckridge 2004, 31). I examine how such laws served as a catalyst for Black cultural production as understood by the standards of Mercer and Spillers and reflect on how the impact of this resistance reverberated throughout the French Empire all the way back to the French courts. Examining historical and contemporary artworks by Marius-Pierre Le Masurier, Louis Antoine Collas, Karine Jones, and Sonya Clark, I argue that creolization emerged within tactics of resistance through hair and dress serving as a crucial site of cultural production and self-determination for the enslaved.

Joana Joachim earned her PhD in the department of Art History and Communication Studies and at the Institute for Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at McGill University working under the supervision of Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson. Her research interests include Black feminist art histories, Black Canadian studies and Canadian slavery studies and her SSHRC-funded doctoral work, There/Then, Here/Now: Black Women’s Hair and Dress in the French Empire, examined the visual culture of Black women’s hair and dress in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, investigating practices of self-preservation and self-care through the lens of creolization. Dr. Joachim has also been appointed as a McGill Provostial Postdoctoral Research Scholar in Institutional Histories, Slavery and Colonialism beginning in the Fall of 2020.

Advertisement for the first English translation of Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (Grove Press, 1967).

B.7.2 ‘Black Skin, White Masks’: Whiteface Performance in the United States

Matthew Teti

In antebellum America, many enslaved Africans and their descendant were forced to perform “cakewalks,” wherein they dressed up in the old clothing and accessories of their masters and pretended to mock them. Such displays served the purpose of the proverbial safety valve, alleviating tension between slaves and slave owners. In the century after the American Civil War, blackface performance, or minstrelsy, emerged as an analogous, but opposite form of entertainment in which white folks blackened their faces and perniciously derided black people, depicting them in a variety of harmful stereotypes. In John Howard Griffin’s sociological project Black Like Me (1961), the author sanitized blackface performance and sought to turn the appropriation of black skin by white actors into a bridge towards racial reconciliation by allegedly exposing “how the other half lives.” However, many, including the writers for Saturday night Live (SNL), and cast comedian Eddie Murphy, saw Griffin’s stunt for what it was: a hokey attempt to connect to historical experience and systematic exclusion, whose real-life effects cannot simply be taken off or washed away. In the pre-taped SNL sketch, White Like Me (1984), Murphy used Hollywood magic to go undercover as a white man in New York City, exposing the racial inequities plaguing contemporary society. Considering examples from Brian De Palma’s early film Hi, Mom! (1970) and the pioneering work of Adrian Piper and Howardena Pindell in the 1970s and 80s, to performance artists Pope.L and Narcissister, this paper will serve as an introduction to the critical reinvigoration of whiteface performance amongst black American artists over the last 50 years. With the aforementioned historical markers in mind, whiteface will be demonstrated to be a poignant tool for exploring racial conflict in the United States, up to and including the current moment.

Matthew Teti is an art historian, writer, and educator, whose work focuses on the United States during the cold war, especially work having to with socio-political themes, such as war, protest, terrorism, civil rights, climate change, and space exploration. Currently an adjunct assistant professor at Cooper Union in NYC, Matthew holds a MA and Ph.D. from Columbia University, where his dissertation on Chris Burden’s early minimalist and post-minimalist sculpture, and his transition to performance art in 1971, won him a fellowship from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation. Matthew has published one academic article on Burden and has another in press (Routledge, 2020). His current research projects include, Minimalist Primitivist: Robert Morris and the Mound Builders; and Who Owns the Future? On Close Encounters and Environmental Neurosis Through the Lens of Johan Grimonprez, which concerns the Cold War American conflation of the Soviet threat, alien invasion, and the climate crisis.

Joseph Obanubi. Within the Circuit, Techno Heads series. Digital, 30 × 30 inches, 2020.

B.7.3 Identity and Fantasy: A Techno Head

Joseph Obanubi, artist

According to theorist Kodwo Eshun, “an Afrofuturist art project might work on the exposure and reframing of futurisms that act to forecast and fix African dystopia” (Eshun 2003, 293). The African dystopia that Eshun references emerged from the mission of colonialism – to separate and conquer – practices that led to the theft of African bodies as well as their cultural heritage. Even as dialogues surrounding reparation are extensively discussed, this dystopia persists in the marginalization and the death of African bodies outside the continent and through self-colonization within. Hence this proposal asks: Can Afrofuturist fantasy, as a form of technological camouflage, work to unmask current global realities while protecting African identity? This presentation will discuss my visual practice, in particular the series Techno Heads and how it explores fragmented montages in the context of globalization and technology. Through these montages immersed in Afrofuturistic or Afro- surrealist environments, an alternative epistemology is formed — one that alters realities and reimagines the freedom of Africans in contemporary society. The body of work focuses on how individuals within the contemporary African society navigate day-to-day patterns of life, infiltrated with technology, even in its simplest form. It shows how contemporary society strongly revolves around and depends on technology for communication, motion, and navigation, all of which are central aspects of human existence. It also touches on the concept of Metaphysics in the African context, exploring how identity, space and time have become intricately linked with even the simplest products of technology and their various forms of camouflage.

Joseph Obanubi (1994) is a visual artist based in Lagos, Nigeria. He studied graphic design at the University of Lagos, Nigeria where he obtained his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in 2015 and 2017 respectively. He currently lectures in his alma mater. He is a multimedia artist whose work questions notions of identity, fantasy/delusion, experimentation, technology and globalization reconstructing fragments found in the everyday experiences. He considers his work to be a visual bricolage—a (re)construction of different subjects taken from their original context into a new one. His creative Ideology stems from delusion, surrealism, futurism and experimentation that hinges on Afro context. Obanubi’s professional projects include Techno Heads (which was shortlisted as part of the finalist for the contemporary African photography prize in 2019 and won the British Council Prize for Emerging Artist in 2019), Wrap your minds around, Altered Reality and Escapes, amongst others.