C.8 Decolonized Art Colonies and Uncooperative Art Cooperatives: Expanding our Understanding of the Modern and Contemporary Art Collective

Fri Oct 16 / 9:00 – 10:30

voice_chat expiredchairs /

- M. Elizabeth Boone, University of Alberta

- Heather Caverhill, University of British Columbia

The term “art colony” typically conjures turn-of-the-twentieth-century rural enclaves where close-knit groups of genteel white male artists assembled to escape the challenges of modern Europe and North America. Art historians Karal Ann Marling (1977) and Margaret Werth (2007) have used the phrase “art colonizing” to align such phenomena—groups of artists who extract value from the land and people, converting them into cultural capital for export elsewhere—with colonial processes. This session seeks to bring together scholars who explore historic and/or contemporary art colonies, cooperatives, and collectives that exist outside of this characterization. Papers might pose questions about intercultural, Indigenous, ethnic, immigrant, religious, regional, or international groups of artists; practices that recover and decolonize the land; collaborative art, design, and craft production; shared political ideas and activism; common financial systems, patronage, and academic or other institutional ties; mobility; or even unproductive art colonies. We welcome papers about different materials, geographies, and theoretical approaches.

M. Elizabeth (Betsy) Boone is Professor of the History of Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Alberta. Betsy is the author of The Spanish Element in Our Nationality: Spain and America at the World’s Fairs and Centennial Celebrations, 1876–1915 (PSUP 2019) and Vistas de España: American Views of Art and Life in Spain, 1860–1914 (YUP 2007). She is beginning a new project on the intersection of art, animals, and agricultural land in the late nineteenth century.

Heather Caverhill is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History, Visual Art & Theory at the University of British Columbia. Her research is focused on nineteenth- and twentieth-century art and photography in the North American West. She recently finished a Terra Foundation Pre-doctoral Fellowship at Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC (2019–2020).

Àsìkò residents taking part in an African dance class at L'école des Sables in Toubab Dialao, Senegal, 2014. Photo by Erin Rice.

C.8.1 The Àsìkò Workshop in Nigeria: Historic Paradigm, New Initiative

Amanda H. Hellman, Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University

The workshop in Nigeria is part of a historical lineage of alternative art education formats that critique the more formal, western education models, which emerged during the end of colonialism and early independence. The Àsìkò Workshop in Nigeria: Historic Paradigm, New Initiative considers the Àsìkò Art School, a recent rethinking of the workshop, created in 2010 by Bisi Silva at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos. Characterized as “part art workshop, part residency and part art academy,” this annual intensive was developed to investigate the way in which the familiar format of a workshop is used to critique the pedagogy, methodology, and artistic practice that came before, while at the same time focusing on the visual implementation of abstract concepts, theories, and converging histories. In service of this vision, artists and curators from all over the continent are accepted to the program to experiment with artistic and curatorial practice. In 2014, Àsìkò took place in Senegal during Dak’Art, the oldest biennial on the continent, articulating the workshop’s commitment to dialogue with an African arts community beyond Nigeria, while responding to the need for improvement within the existing post-colonial arts education infrastructures. Since then, the workshop has been held in a different country nearly every year and has published Àsìkò: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa, a volume collating the achievements of each iteration between 2010 and 2016. The fundamental issue this initiative addresses is how the crossroads of Western formal educational models, post-colonial discourse, pan-African heritage, and the specificities of Nigeria’s political and cultural history can be navigated to productive artistic and discursive ends.

Dr. Amanda Hellman is the curator of African art at the Michael C. Carlos Museum of Emory University. Her upcoming exhibition, And I Must Scream, features contemporary artists who use the visual trope of the monster to examine inconceivable acts such as environmental destruction, displacement, human rights violations, and corruption. Other exhibitions include DO or DIE: Affect, Ritual, Resistance, The Carlos as Catalyst, and Between the Sweet Water and the Swarm of Bees. Her research on museum development in West and East Africa reveals how heritage formation and artistic practice are inextricably linked. Most recently she has published Die and Do: Egungun as a Form of Resistance and Recovery, in Visible Man: Fahamu Pecou and To Store is to Save: Kenneth C. Murray and the Founding of the Nigerian Museum, Lagos, in Museum Storage and Meaning. Amanda received a B.A. from Georgetown University, an M.A. from Williams College, and an M.B.A. and a Ph.D. from Emory University.

Aka Høegh, Udsyn – Indsigt (Outlook - Insight), 1993-94. Photo: David Norman.

Peter Kujooq Kristiansen, Birdie, 2000. Photo: David Norman.

C.8.2 Stone and Man’s Common Ground: Land Collectives in Kalaallit Nunaat

David W. Norman, University of Copenhagen

In the south Greenlandic town of Qaqortoq, a sea of faces peers down from a small cliff. This series of reliefs, carved directly into exposed bedrock, is one of Aka Høegh’s contributions to Stone and Man, the collaborative sculpture project she launched in 1993. Høegh initially invited eighteen Greenlandic and Nordic artists to produce public works in her home community over two summers. In subsequent years as others joined the project, Stone and Man has grown to encompass nearly all facets of town life, stretching from tourist sites to garbage dumps and the courtyards of outlying public housing. In this paper, I examine the collaborative relations informing Stone and Man’s production and its immersion into Qaqortoq’s social fabric and compare these with the forms of collective land stewardship envisioned by the communal movement known as Aasivik, ongoing since 1976. Invoking a name used to designate summertime gathering spaces, the movement brought together artists, hunters, and political activists seeking to reinvigorate collective life in non-urban settings as Greenland was on the cusp of achieving Indigenous self-governance. I take lessons from this activist tradition to examine how the artists behind Stone and Man approached Qaqortoq’s earthy infrastructure as a social surface, not just the site of an intervention but a ground that mediated across social and cultural divides. By framing the earth’s interfacing abilities as a prerequisite for collaboration, Stone and Man and Aasivik raised the possibility of understanding land as a participant in social action.

David Norman is a PhD candidate in the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen. His dissertation examines Greenlandic Inuit artists’ earliest forays into land art, video and intermedia in the 1970s-1990s, a period when Greenland achieved self-governance after nearly three centuries as a Danish colony.

A painting class at Winold Reiss’s West 16th Street Studio, 1928. Photo: Suzuki Studio.

C.8.3 The Winold Reiss Studio as a Hub of Transcultural Modernism

Julie Levin Caro, Warren Wilson College (Asheville, NC)

This paper examines the unique character and influence of the Winold Reiss Studio as an art school, portrait studio, graphic and interior design workshop, and crucible of transcultural modernism. Located in New York’s Greenwich Village from the mid-teens to the 1930s, Reiss’s studio was a stage on which he performed the roles of art teacher, multinational portraitist, European modern designer, and catalyst of cultural exchange. Because of his range of artistic talents and the presence of his European, African American, Mexican, and Asian American artistic friends, Reiss's studio became a crossroads where artists, writers, musicians, and intellectuals from many different countries and walks of life met, partied, and transformed their art practices. Drawing from historic photographs of the Reiss Studio, first-hand accounts from his students and new materials uncovered in the Winold Reiss Archives, I describe the content and style of Reiss’s pedagogy and the opportunities he provided for individual expression and artistic collaboration. For example, I recontextualize the work of Aaron Douglas, the leading African American artist of the Harlem Renaissance, within the transnational artistic context of the Reiss Studio. Like his fellow members of the Reiss Circle in the mid-1920s, including Hans Reiss, Erika Lohman, and Henriette Reiss, Douglas drew from a shared vocabulary of modernist pictorial forms inspired by Winold Reiss’s portraits and interior and graphic design work. The contributions of this diverse group of artists allows for a re-mapping of the physical, cultural, and artistic terrain of the Harlem Renaissance and American Modernism.

Julie Levin Caro is Professor of Art History and Chair of the Art Department at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina. She received her doctorate in Art History from the University of Texas at Austin. A specialist in modern American art and African American art, Caro has published on the WPA-era paintings of Allan Rohan Crite and the contemporary stain glass window designs of Jean Lacy. Her essay Allan Crite’s [Re]Visioning of the Spirituals appears in the anthology, Behold: Representations of Christ and Christianity in African American Art published by Penn State Press. Caro is also active as a curator, and some of her exhibitions include Freedom of Expression: Politics and Aesthetics in African American Art, Gee’s Bend: From Quilts to Prints, Between Form and Content: Perspectives on Jacob Lawrence and Black Mountain College, and From Bauhaus to Black Mountain: Josef and Anni Albers.

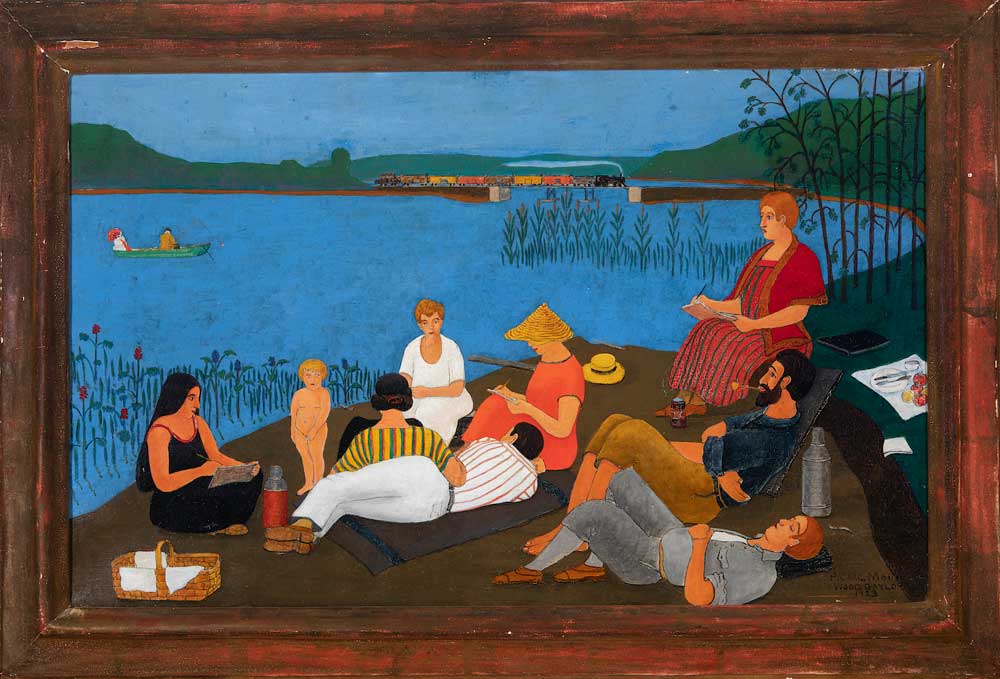

Wood Gaylor, Picnic, Shaker Lake, Alfred, Maine, 1923. Oil on canvas in hand-carved frame by Robert Laurent. Courtesy of Bernard Goldberg Fine Arts, LLC, New York.

C.8.4 Wood Gaylor, the Ogunquit Art Colony, and American Primitivism

Andrea P. Rosen, Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont

American artists who frequented the colony in Ogunquit, Maine, in the 1920s were among the first collectors of objects that would come to be collectively defined as American folk art. By embracing early and rural American art and craft, these artists sought to validate an inherently American modernism, as they reacted to increasing nationalism after World War I with a move away from the European “isms.” Implicitly, the rejection of the European avant-garde in favor of an American folk art–based primitivism was also a rejection of European forms of primitivism based in non-Western tribal artifacts. The work of overlooked Ogunquit attendee Wood Gaylor (1883–1957) serves as a case study: after exhibiting an indebtedness to European primitivists in his early work, Gaylor developed a signature style of bright, outlined figures with little shading, an approach for which he found affirmation in the flattening and distortion of American folk painting.

It is notable that the American “primitive” inspirations for the Ogunquit colonists consisted of the material culture of European settlers and their descendants, rather than that of indigenous Americans. In what ways was their choice of Euro-American folk material culture, in lieu of both global and American indigenous art, motivated by racial as well as national identity? Did seeking antiques that could reinforce the “American-ness” of their art also require constructing and reinforcing the “whiteness” of America’s rural past? Was collecting artifacts by white craftsmen that depicted Native Americans (“cigar store Indians”) a way to co-opt the image of the “primitive” even as they ignored the production of non-white makers? As primitivism requires the creation and use of a dialectical “other,” in what ways were the folk art producers of rural Maine “otherized,” if not in the racial and geographic terms that European primitivists deployed?

Andrea P. Rosen is the curator of the Fleming Museum of Art at the University of Vermont. Rosen holds an M.A. in art history and museum studies from Tufts University and a B.A. in studio art from Smith College. She curated and authored the catalogue for the exhibition Wood Gaylor and American Modernism, 1913-1936, organized by the Fleming Museum, which will travel to the Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York, and the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, Ogunquit, Maine in 2021. She has curated and co-curated a wide range of exhibitions, including shows on historical and contemporary miniatures, Victorian fashion, cartoonist Alison Bechdel, Afro-Atlantic sacred art, Asian art, and Surrealist photography. She is the founder of the Vermont Curators Group, a venue for collaboration among the state’s curators.