D.8 HECAA: Historians of Eighteenth-Century Art and Architecture

Fri Oct 16 / 11:00 – 12:30

voice_chat expiredchair / Christina Smylitopoulos, University of Guelph

HECAA works to stimulate, foster, and disseminate knowledge of all aspects of visual culture in the long eighteenth century. This open session welcomes papers that examine any aspect of art and visual culture from the 1680s to the 1830s. Special consideration will be given to proposals that demonstrate innovation in theoretical and/or methodological approaches.

Christina Smylitopoulos is Associate Professor in the School of Fine Art and Music and Faculty Curator of the Bachinski/Chu Print Study Collection. She has essays in L’Image railleuse: La satire visuelle du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours; RACAR; The British Art Journal; 18th-C Life; Word and Image in the Long 18th C; Hats Off, Gentlemen; edited Agents of Space; Spaces of Wonder, Wonder of Space (a winner of the 2019 Leab Exhibition Catalogue Award); Artful Encounters: Sites of Visual Inquiry; and co-edited (C. Ionescu) issue 39 of CSECS’ Lumen. She is completing Publishing ‘Pioneer’: Thomas Tegg, Graphic Satire, and the Aesthetics of Modernity and has grants/fellowships from, among others, SSHRC; the Ministry of Science, Research, and Innovation; the Lewis Walpole Library; the Huntington Library, the Swann Foundation for Caricature and Cartoon, and the Houghton Library. She has reviewed for Oxford Art Journal, RACAR, The Historian, University of Toronto Quarterly, and caa.reviews and teaches in the MA.AHVC.

The Chelsea-Derby-imitation vase fired in Jingdezhen, China, circa 1785. (The V&A Collection, London, UK, accession number: C.92-1963).

D.8.1 Chinese Occidenterie: Reproducing the Aesthetics of Otherness in China’s Long Eighteenth Century

Chih-En Chen, SOAS University of London

The assemblage of objects by the Qing imperial household was not only an account of the emperor's taste but also advocates the imperial understanding of the world's cultural heritage. The present article contemplates an issue regarding the existence of an exquisite group of artworks named by yang 洋, including yangqi 洋漆and yangci 洋磁, which conceptually refer to the imported foreign ware, abundantly documented in the Qing imperial workshop records, yet remains ambiguous regarding its ontology. The Chinese character yang stands for the aesthetics of otherness; in other words, an expression of exoticism. From the beginning of the Yongzheng reign (1722-1735 CE), commissioned directly by the emperors, the Qing imperial workshops and the Jingdezhen imperial kilns had been making the replica of yangqi and yangci, which were addressed by jia 假 (fake) or fang 仿 (imitation), such as jia yangqi and fang yangci. The vast quantity and ethereal quality of the replica dominated the High Qing period and made their way into the collection of the Qing imperial household. The Chinese prefixes, jia and fang, therefore, became the signifiers bearing the imperial connoisseurship. Moreover, the replica of this genre became a trendy replacement to those imported wares, and the nomenclatural boundary between the domestic manufactured and the oversea imported began to blur. By attending not only to the nomenclature but also the characteristic of the yang objects, this research aims to examine the connoisseurship, adaption, and acceptance of the “non-authentic” artifact bearing exotic surface assorted in the Qing imperial household during China’s long eighteenth century.

Chih-En Chen is a PhD Candidate at the Department of the History of Art and Archaeology at SOAS, University of London. Before the arrival of his current position, he worked at Christie’s Toronto (2013-14) and Waddington’s Auctioneers (2014-17). Specialized in Asian ceramics and history of art in a global context, he has been consulted by museums and private funds, awarded The Joseph-Armand Bombardier CGS Doctoral Scholarships (2017-20), GSSA Fellowship (2018-2019), The BADA Friends Prize in Memory of Brian Morgan (2020), The Oriental Ceramic Society (OCS) George de Menasce Memorial Trust Award (2020), and The Chiang Ching-Kuo CCK Fellowships for Ph.D. Dissertations (2020-21).

Nicolas Lancret, Four Seasons: Winter, 1719-21, oil on canvas, 115 x 94 cm, Private Collection.

D.8.2 The Fall of Allegory in Eighteenth-Century French Painting: The Case of Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743)

Sofya Dmitrieva, University of St Andrews

Eighteenth-century French art writings were characterized by a devastating critique of the allegorical in painting. Critics, most famously Jean-Baptiste Dubos and Denis Diderot, accused it of artifice and advised artists to avoid allegory in their practice. Independently, allegorical painting rapidly went out of vogue. From about the 1720s on, it was produced mainly for decorative purposes: when it came to adorning royal residences or aristocratic hôtels, traditional cycles like Four Seasons and Four Elements were, perhaps, the first thing that came to the mind of the commissioners. Though even when artists chose to address such subjects or were ordered ones, instead of using the conventions of allegorical painting, they appealed for the help of other genres. One of the first artists to treat allegorical subjects in this unconventional manner was Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743). Lancret turned to allegorical series repeatedly throughout his career: he created cycles of Four Elements (1730-32), Four Ages of Man (1733-34), Four Times of Day (1739-41) along with several series of Four Seasons (1719-21, 1723, 1738, and 1742-43). All of them took on a form of genre paintings.

The scholars of Lancret have done major work on building the artist’s oeuvre into the preceding tradition by revealing the painter’s borrowings from seventeenth-century iconography. My argument, meanwhile, is that Lancret’s use of allegory differed from that of his predecessors much more than resembled it. In order to demonstrate the innovativeness of the artist’s approach, the paper will prove that, first, Lancret’s allegorical cycles could be read interchangeably as allegories and genre pieces and, second, that each painting constituting them was to the same extent a part of a series as it was a self-standing artwork. The paper will conclude by revealing how Lancret’s developments were characteristic of eighteenth-century French painting as a whole.

Sofya Dmitrieva is a PhD Art History student at the University of St Andrews. She specializes in eighteenth-century French painting, with an emphasis on spectatorship and genre theory. Dmitrieva holds a BA from the Higher School of Economics (Moscow) and an MLitt from the University of St Andrews. Her doctoral research is funded by the Wolfson Foundation.

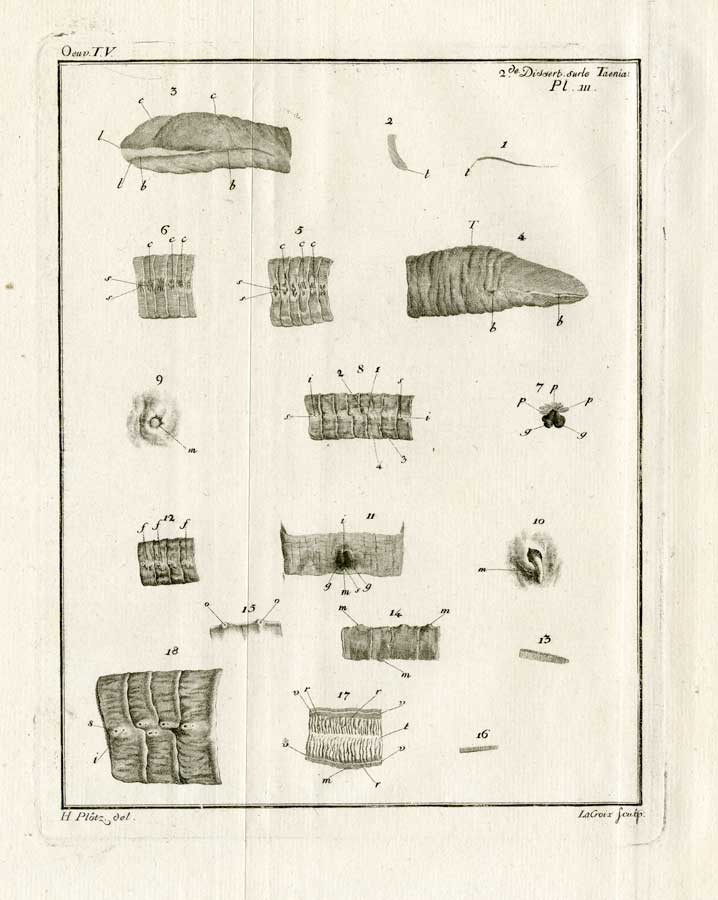

Henri Plötz, Tapeworms; plate III in Charles Bonnet's Œuvres d'histoire naturelle et de philosophie, t. 1. Neuchatel: Chez S. Fauche, 1779 [orig. 1777]. Image courtesy of Bruce Peel Special Collections & Archives, University of Alberta.

D.8.3 Portrait of an Eighteenth-Century Tapeworm: Efforts to See and Image an Elusive Subject by Naturalist Charles Bonnet (1720-1793) and Artist Henri Plötz (1747-1830)

Lianne McTavish, University of Alberta

The tapeworm, an intestinal parasite remarkable for its length and tenacity, was famous during the eighteenth century. Written and visual representations of the worm were featured in over 49 European treatises, produced by the most respected physicians, anatomists, and naturalists of the day. Genevan naturalist Charles Bonnet was eager to enter ongoing debates about the elusive tapeworm, asserting that his methods of attentive looking would correct errors about the worm’s anatomical structure. His three publications on the tapeworm (1750, 1777, and 1780) have nevertheless received scant attention from modern scholars, in part because they were largely mistaken about the body of the tapeworm, misidentifying its head and mouth. Despite these errors, Bonnet’s texts are worthy of art historical analysis, for they reveal the naturalist’s efforts to see and know the worm, shedding light on the visuality of eighteenth-century naturalism. Most striking, however, is Bonnet’s rare and detailed account of the crucial role played by an artist in the production of knowledge. The Danish miniaturist and portrait painter, Henri Plötz, worked alongside Bonnet as a collaborator for seventeen years (1770-1787). Bonnet describes how the artist scrutinized tapeworm specimens using his naked eye, a magnifying loupe, and a microscope, gazing at and handling the worm pieces. Bonnet used drawings to guide the visualizing process, arguing that the images created by Plötz were the most valuable outcome of their collective labour. My talk will analyze this striking narrative of tapeworm research to highlight the active participation of an artist in early modern experiments. Plötz used multiple methods to observe the worms before producing images that were meant to shape meaning rather than represent the discoveries of his patron.

Lianne McTavish is Professor of the History of Art, Design, and Visual Culture in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta. She offers courses in early modern visual culture and critical museum theory. Her research has been generously funded by, among other sources, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Killam Research Fund. McTavish has published over 40 refereed articles and chapters, and has published three single-authored refereed monographs, including Childbirth and the Display of Authority in Early Modern France (Ashgate, 2005) and Defining the Modern Museum (University of Toronto Press, 2013). Her fourth book, Voluntary Detours: Small Town and Rural Museums in Alberta, is in press with McGill-Queen’s University Press. McTavish regularly curates exhibitions of contemporary art, including FLUX: Responding to Head and Neck Cancer at the International Museum of Surgical Science in Chicago (2018). Her current obsessions include early modern intestinal worms and modern pioneer museums.

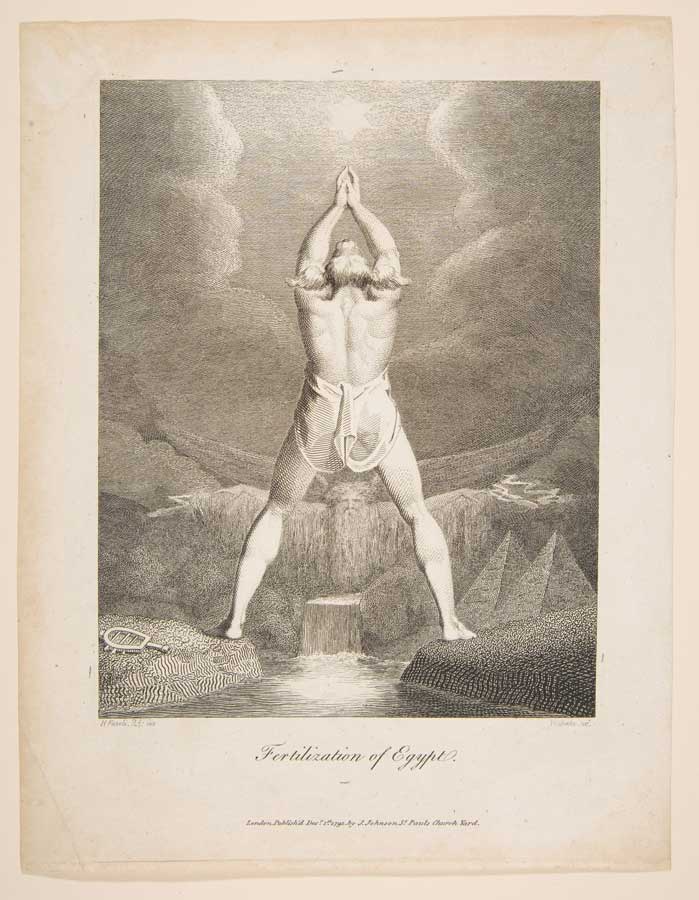

Fertilization of Egypt, from Erasmus Darwin's The Botanic Garden, William Blake after Henry Fuseli, 1791, engraving, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1968.

D.8.4 Thinking through Collaboration: The Fertilization of Egypt

Sarah Carter, McGill University

In the advertisement to Erasmus Darwin’s poem, The Botanic Garden (1791), the author explains his purpose “to inlist Imagination under the banner of Science.” Modelling Darwin’s skillful use of “loose analogy” to encourage the reader toward philosophy, the text’s striking visuals project outward into Enlightenment scholarship to situate the work in a vibrant discourse of comparative mythology. Proceeding from a close visual analysis of the engraving The Fertilization of Egypt and its preparatory drawing, I argue that this collaboration between artists Henry Fuseli and William Blake not only enriches the allegorical mode introduced in the verse but mobilises ancient “Egyptian remains [to] lead us into unknown ages.” Triangulating between Darwin, Fuseli and Blake, this paper resists the temptation to determine whose vision emerges most discernibly in the engraving and considers the interpretive potential of a collaborative image-making practice. This egalitarian analytic overturns assumptions about “style” and allows us to better understand the conceptual and aesthetic framework that gives the image its generative force – its ability to evoke a complex network of associations in the mind of the viewer. Finally, this method invites us to explore a diverse range of meanings for ancient Egyptian material culture in the late eighteenth century.

Sarah Carter is a PhD candidate in the Art History and Communication Studies Department at McGill University. She was the recipient of the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies’ Mark Madoff Prize (2019) for her essay 'Our Modern Priapus': Thauma and the Isernian Simulacra, which was published in the Society’s journal Lumen (39, 2020). Her research is funded by a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholarship.