C.6 Early Modern Landscape and Eco-Critical Perspectives

Fri Oct 20 / 13:30 – 15:00 / KC 208

chair /

- Joseph Monteyne, University of British Columbia

Stephen Eisenman has recently suggested that the essential question for art history today is whether the challenge of the Anthropocene—the epoch when earth systems have become so degraded that human survival itself is in doubt—demands a re-evaluation of the art and culture of the past, and even a reconsideration of current methods of scholarship. This session hopes to query what effect this pressing crisis has on our connections to historical objects and events from the early modern period (1400-1800) by focussing on the genre of landscape from an eco-critical perspective. Papers in this session focus on the material aspects of nature, ‘naturecultures’, gardening tools and images of cultivated landscapes, rural immersion and allegories of artmaking, land enclosure and violence, as well as colonial ecotourism in eighteenth-century India.

keywords: early modern landscape, eco-criticism, material aspects of nature, naturecultures

session type: panel

Joseph Monteyne is an Associate Professor of Art History who teaches the Renaissance art and media cultures of Italy and Northern Europe, the spectacle of Counter-Reformation Rome, the art and culture of Spain and Spanish America, as well as the art of Northern European urban and courtly cultures of the 17th century. He has published three books on early modern British print culture, and has recently been leading graduate seminars on early modern transhumans, animals, and monsters, and ecocritical perspectives on early modern visual culture.

Pieter Breughel the Younger, Spring, c. 1620-1630. Oil on panel, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (238.2015), Canada.

Shaping the Landscape: Recreating Watering Vessels from Early Modern Europe

- Ellen Siebel-Achenbach, University of Toronto

Developed and operated by human hands, tools shape the landscape. My paper examines watering vessels in the European Early Modern Period as indicative of human interference with the natural landscape in both agricultural and aesthetic pursuit. As well as archaeological evidence, the visual culture surrounding watering vessels suggests their role as symbols of “cultivated” landscapes (against “wilderness”) within the growing popularity of Early Modern garden culture. I draw a key distinction between (modern) environmentalism and naturalness: while the collection of rainwater in a barrel, for instance, is environmentally friendly, it is also an unnatural process that manipulates the natural elements of earth and water. My examples of watering vessels are drawn from archaeological artifacts, technical designs (both drawn and printed), and artistic depictions within narrative/portrait contexts. Through these sources, I will recreate several watering vessels based on chantepleure (thumb pots with possible handles), watering pots (distinguished by spouts and roses), and watering barrel designs. These recreations will allow me to consider the physicality and functionality of these tools, as well as what they can tell modern makers and audiences about interactions between “natural” and “unnatural” materiality in the landscape.

keywords: gardening tools, garden culture, watering tools, recreation, cultivated landscapes

Ellen Siebel-Achenbach has recently finished an undergraduate degree at the University of Waterloo with a joint-major in Visual Culture and Medieval Studies and minors in Fine Arts Studio and Church Music and Worship. In the fall, they will begin a master’s degree in art history at the University of Toronto (with a Canada Graduate Scholarship), with the intention to further pursue research into tool and craft heritage in medieval and Early Modern Europe. This research has combined visual/historical theory with reimagined/recreated material culture through traditional carpentry and textile processes of making. Ellen Siebel-Achenbach has previously given two conference papers on this topic, the most recent of which was presented at the International Congress of Medieval Studies (May 2023).

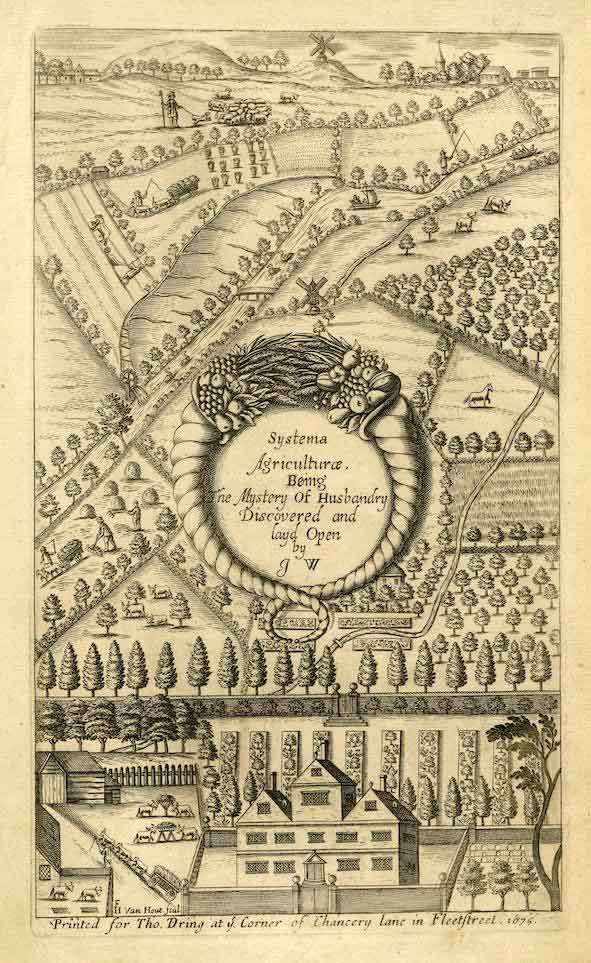

Frederick Hendrik Van Hove, frontispiece for John Worlidge, Systema Agriculturae: Being the Mystery of Husbandry Discovered and Layd Open by J W (London, Thomas Dring, 1675), engraving, London, British Museum

They Ball-Beat their Swords into Ploughshares: Picturing the Violent Fracturing of the Holistic Ecosystem in Early Modern Britain

- Sarah Mousseau, University of Guelph

It has been widely acknowledged that the success of capitalism required a change in how humans understood and rationalized the non-human world in order to move from a system of subsistence to one of accumulation. Scholars have described this phenomenon in various ways, but generally it can be seen as a splitting or moving away from a pre-modern holistic worldview in which humans and non-humans co-exist within an interdependent ecosystem towards an early modern cartesian binary in which humans are the dominant species over the non-human world – thus allowing for aggressive exploitation of natural resources for profit. An important step towards participation within the English capitalist experiment was the privatization of common lands for personal gain. The legal concept of property was extended to include land and goods located on or taken from the land – including those produced by the land. Physical objects like houses, gardens, and barriers were built and dug into the landscape as signifiers of ownership. Patrons sought visual records of absolute ownership in the form of prospect paintings while the rise of illustrated DIY guidebooks demonstrate a heightened interest in land improvement and productivity. These early modern changes to the landscape were brutal and swift – profoundly impacting the way that rural working classes lived and thought of themselves within the world. This research examines how the early-modern English land enclosures that took place in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are represented in visual art as deliberate and violent actions that fractured the pre-modern holistic ecosystem worldview.

keywords: early modern landscape, land enclosures, eco-criticism, capitalist practices, naturecultury

Sarah Mousseau is a graduate student at the University of Guelph where she is pursuing her Masters of Art History and Visual Culture with a specialization in gender representation in eighteenth-century British print culture. Her research interests include medieval and early modern book and print culture as well as the function of visual culture as a site for social control and resistance. She holds a diploma in Film and Television Production from Humber College and a Bachelor of Arts Honours degree from the University of Guelph. She was awarded a Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada Scholarship as well as an Ontario Graduate Scholarship for her work examining the development of the constructs of identity (including race, gender, and sexuality) and alcohol consumption in British and settler-colonial visual culture.

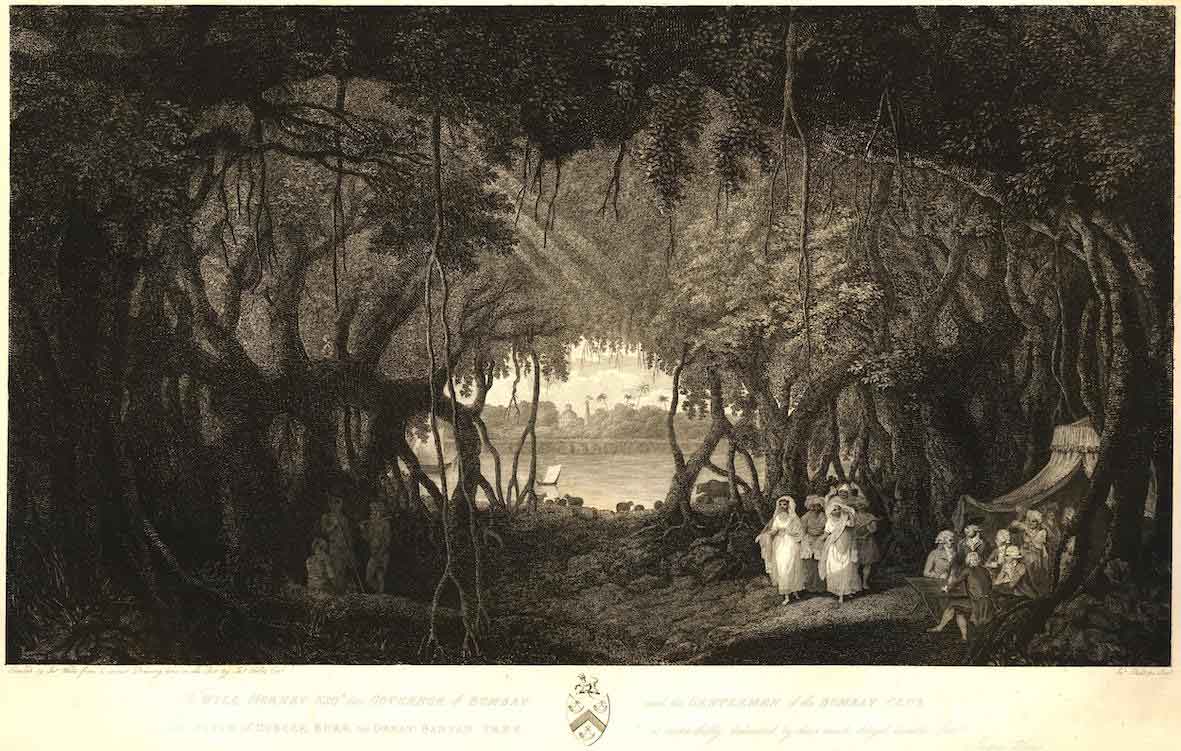

James Phillips after a painting by James Wales (after a drawing by James Forbes), Cubeer Burr the Great Banyan Tree, 1790, etching. London, British Museum.

James Forbes and the Paradox of India

- Sarah Carter, University of Chicago

Banyan trees and Hindu cave temples featured prominently in British depictions of India in the late eighteenth century. These exotic species and ancient spaces became “primeval ciphers” for a past that was perceived to have endured into the early modern era (Ray 2013). James Forbes’s Cubeer Burr, The Great Banyan Tree (1790) [Fig. 1] and its pendant The Temple of Elephanta (1790) [Fig. 2] have been read in these terms—as picturesque or sublime visions of a wild and primordial India that British agents aspired to tame and “improve” through colonial management. This paper, however, shifts emphasis from aesthetics to ecology. I read Forbes’s prints alongside his unpublished manuscripts and travelogue Oriental Memoirs (1813–1815) to illuminate how colonial agents negotiated the complexities of South Asian environments—at once hostile and wondrous. I argue that Cubeer Burr and The Temple of Elephanta are visual evidence not only of Forbes’s heterogeneous lived experiences but also of a broader cultural paradox that evolved in tandem with Britain’s expanding colonial reach: the fact that “India” recalled both an “ever-flourishing garden” (Czennia 2021) and diverse “deathscapes” (Arnold 2015) in British imaginations at home and abroad. Being attentive to this paradox allows us to make sense of the perplexing contrariness of a print like Cubeer Burr which suggests the pleasures of ecotourism even as it visually registers the dangers of the “narrow glens, dark woods and impenetrable jungles” that Forbes navigated in his role as a writer for the East India Company. Finally, the paper reflects on how early modern ideas about the natural world forged through colonial encounters have shaped our present, seemingly irreconcilable relationship with nature.

keywords: British empire, India, ecocriticism, landscape, print

Sarah Carter is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago. Her research is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (FRQSC). Her current project is entitled “Empire follows Art”: Trafficking Culture in Imperial Britain 1780–1830. It examines the sourcing, transport and integration of art from India into British collections. Sarah holds a PhD in Art History from McGill University, where she completed a dissertation entitled “Art and Eros in the British Enlightenment” in 2022.