E.1 Convergent Temporalities on the Printed Page

Sat Oct 21 / 8:30 – 10:00 / KC 202

chair /

- Emily Cadger, University of British Columbia

Print media as a medium is soaked in temporal contradiction. Not only did printed images participate in a complete reformulation of past, present, and future that accompanied the emergence of modernity, they altered time consciousness and opened new avenues in which to engage with ever expanding debates about social understanding of time. This session explores representations of the temporal and how artists grappled with emerging theories and philosophies that arose around the visualization of time. The linear, the spatial, the imaginative, as tools of picturing anxieties around, or engagement with, shifting temporalities and our social understanding of them are all of interest. The contradiction inherent to the printed image, concretely capturing the momentary through an ephemeral object, and the ways in which printmakers and publishers could play with multiple temporalities are avenues of scholarship that will be considered.

keywords: print media, time, satire, allegory

session type: panel

Emily Cadger is a PhD student in the Art History, Visual Art and Theory program at the University of British Columbia. Her research looks at the use of fairies and mythological figures as allegorical conduits for new scientific and political knowledge in Victorian art and visual culture. Drawing on works from the Arts and Crafts, Pre-Raphaelite, Socialist, and Suffragette movements her past research has looked at the role of illustrated children's book in constructing national identity and the use of botanical exchange between England and the colonies in relation to gender politics. She holds a SSHRC Doctoral Research Award and is currently the Canadian Graduate Representative for NAVSA.

Francis Barlow, Fable 44 : 45 from Aesopics, or, A Second Collection of Fables. 1668, etching, 25.8 x 18.9 cm. British Museum, London.

Beasts, Brutes, and the Blurry Boundary Between Them: The Power of the Aesopian Fable in Seventeenth Century Early Modern England

- Richard Chapplow, University of British Columbia

Seventeenth century Europe saw a shift to the practice of direct observation of the world as opposed to the reliance on ancient texts. Of great concern for many philosophers, scientists, and theologians was the relationship between humans and non-human animals. René Descartes strengthened that divide in 1637 by stating that only humans were capable of reason and language through their God-given “rational soul” which animals lacked, making animals mere biological automata. The refutations of Descartes were seen in many forms, but it was within English printing, specifically John Ogilby’s editions of the Fables of Aesop that we were presented with rather striking examples. For it was within his printings of Aesop, that Ogilby directly questioned the relationship of humans with animals through the text of his frontispieces, but also shifted the fables’ accompanying illustrations to speak to the blurry, slippery boundary between human and animal.

Although modern versions of Aesopian fables tend to be populated with anthropomorphized animals, this was not the case in the past. Even though the animals in the fables could speak quite eloquently, they were typically shown as they would be seen in nature. Ogilby, with natural history artists such as Francis Cleyn, Wenceslaus Hollar, and Francis Barlow, shifted the animal forms to a hybrid state with animals walking upright and wearing human clothing. It was through the entertaining power of the fable and allegory that Ogilby was able to make rather pointed critiques of the scientific, philosophical, and theological thinking of the time.

keywords: print media, fable, allegory, hybridity, empiricism

As a lifelong consumer of horror in various media, Richard Chapplow’s MA thesis saw him focus on the materiality of painting with regard to images of animal flesh and meat. To remain in the same vein of examining animal bodies, Richard turned to the fables of Aesop and discussions of the boundary between humans and non-human animals brought forth by Descartes and de La Mettrie in his PhD studies at the University of British Columbia.

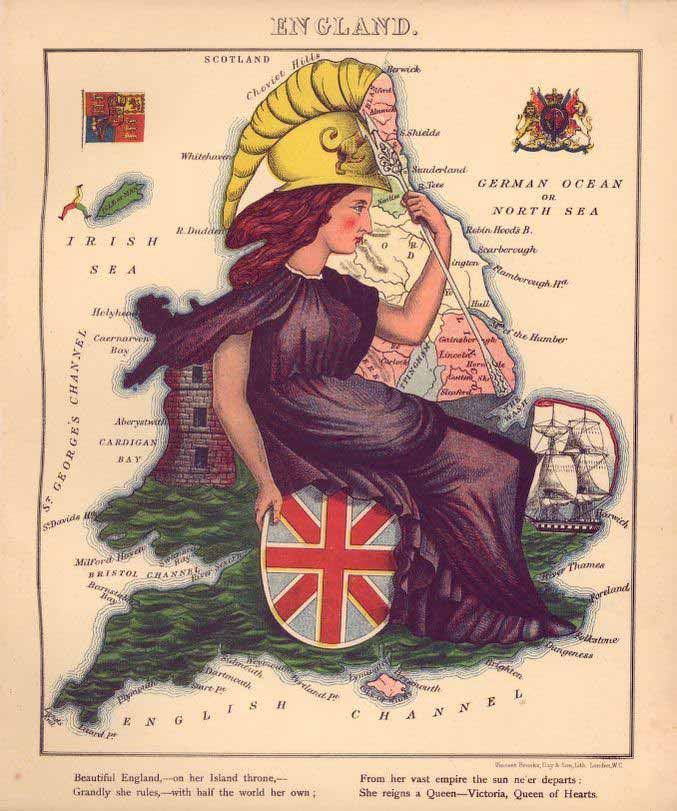

Lilian Lancaster (Tennant), "England," 1868, in Geographical Fun! Being Humourous Outlines of Various Countries by Aleph (William Harvey) (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1868). Map on paper, 28 cm x 23 cm, Stanford: David Rumsey Map Collection.

Anthropomorphic Maps from 19th Century England: Spatiotemporal Narratives of National Identity

- Kristina Parzen, Concordia University

Maps are both spatial and temporal objects. Their relation to space is readily apparent but time is often overlooked by both mapmakers and viewers. Most maps tend towards representing monochronous time or one temporality (Ferdinand 2019, 69). Other maps represent space that altogether avoid time. Such methods of representation are criticized by map historians as creating a false impression of an eternal present (Harrower 2015, 1528; Muehrcke 1998, 160–78). However, there are some maps that identify the geographic present by referencing the historic and even, the mythical past. In nineteenth-century England, a striking type of fantastical map became popular: one which combined, and sometimes even conflated, human forms with cartographic representations of territory. England, for example, took the form of Britannia, seated on an “Island throne;” Italy was represented as Victor Emmanuel II, King of the united country; and Germany took the image of the Pied Piper from Germanic folklore. These anthropomorphic maps, which have their own rich history dating back to the 14th century, represent a fascinating interplay between how narratives of the past shape contemporary national identity bound to geographic space. Focusing on the work of English artist Lilian Lancaster (later Tennant) who produced a diverse collection of such maps, this paper examines the relationship between the spatial representation of the historic and mythical past and their role in constructing national identity. It asks how Lancaster mobilized caricature and allegory as visual narrative devices to tell stories of identity. And it explores how her simultaneous referencing of the historical past, the mythical past, and the geographic present, constructed an English view of national types in Europe. Ultimately, I argue that despite being static objects with fixed representations, Lancaster’s anthropomorphic maps are also active tellings of national identity grounded in space and time.

keywords: anthropomorphic maps, allegory, caricature, national identity, spatiotemporal narratives

Kristina Parzen is a PhD student in Art History at Concordia University, Montreal. Her dissertation research examines the history of anthropomorphic maps produced in Europe since the 14th century. She has presented work at the annual Council for European Studies International Conference and her research is currently funded by a Canada Graduate Doctoral Scholarship provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Antonio Tempesta, Age of Iron, etching, 1599, 22.1 x 33.7 cm, British Museum

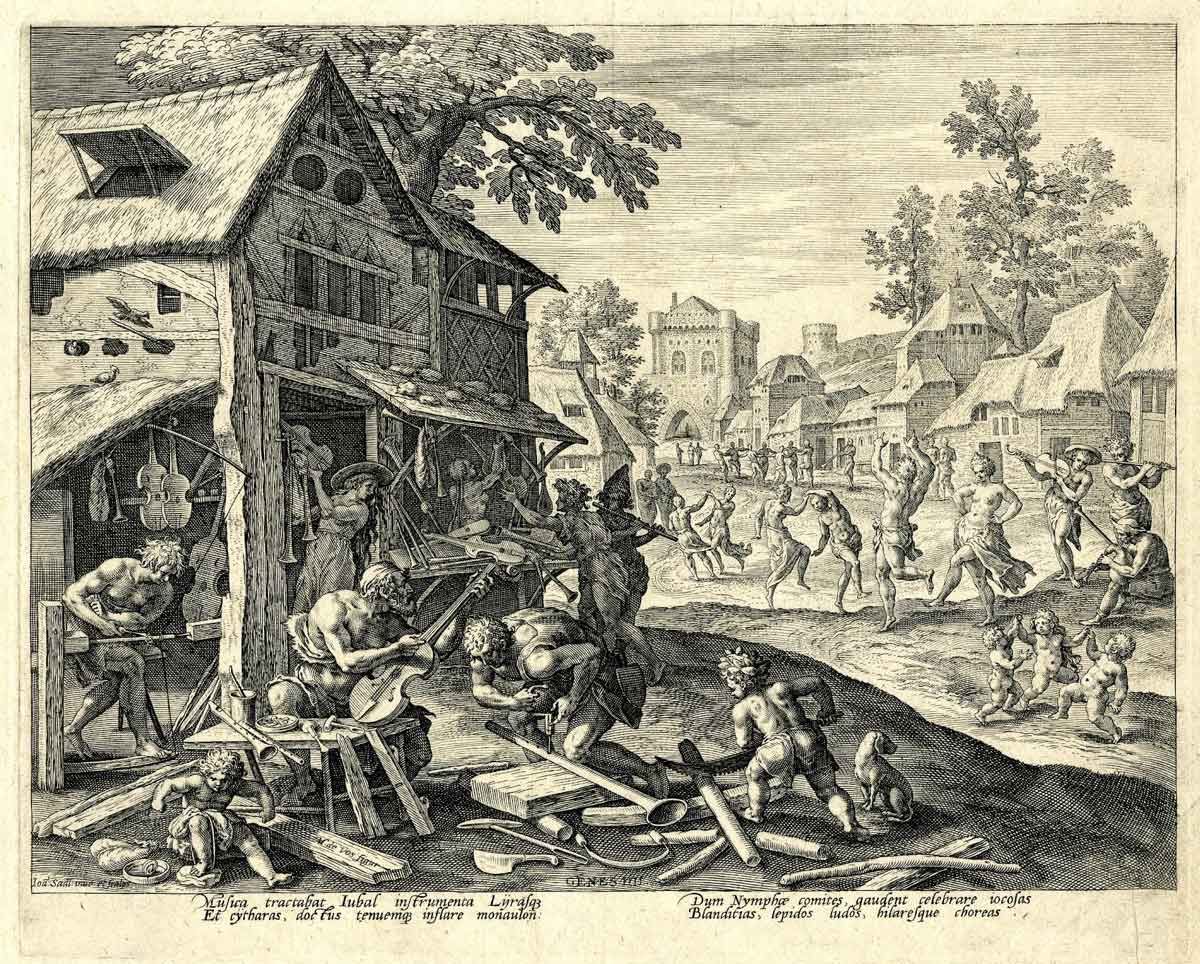

Jan Sadeler after Marten de Vos, Jubal and his Musical Instruments, Engraving, 1583, 20.2 x 25.0 cm, British Museum

Time Made Material: Artifactuality in Early Modern Allegorical Prints

- Timothy McCall, University of British Columbia

Printed series like The Ages of Man illustrate classical poems concerning the history of humanity. Based on the works of Hesiod and Ovid, these images envision humanity in degradation. An ancient golden age is free of trouble or toil. The most recent iron age, which Hesiod and Ovid claimed they lived in, is defined by violence and terror. In Antonio Tempesta’s series The Four Ages of the World (1599), anachronistic iron age belligerents wear courtly fashions and tote firearms. Episodes from the deep biblical past too were reanimated as contemporary scenes, such as Johann Sadeler’s Boni et Mali Scientia (1583). Here, technological innovation is considered in a favorable light compared to the social degradation thematized in The Four Ages of Man. In prints such as these, artists developed the signs and symbols of technological progress, producing a notion of archaeological artifacts leading to modern sophistication. Time, rendered through artifacts, is objectified. Although the discourse of materialized history was developed in illustrations of myths, these temporal resources were fundamental to liberal and modern concepts of history: the bronze and iron age still constitute the epochs of human history.

Comparison to paintings of the same scenes shows far fewer intrusions of the present into ancient stories suggesting that painting conforms to text while prints follow a different procedure to confirm their veracity. Printed images gain their authority from an appeal to eye-witnessing. Thus, they are not typological renditions of texts but rather a visible and self-apparent conformity with the reality, present and local, of its buyer. This paper offers a critical account of the complex relationships between image, medium, and time staged by early modern anachronistic prints.

keywords: allegory, temporality, early modern, print, anachronism

Timothy McCall: I study early modern art theory and printmaking, in which intersections of global encounter and media revolution radically reformulated the concept and reality of "human". How does the early modern campaign to derive a notion of art through a (re)theorization of making alter the broader terrain of labor in entangled domestic and colonial contexts? I am interested in shifts in iconographic tendencies that reveal fundamental recharacterizations of body concept and the emergence of new subjectivities from the dense sea of early modern artifice churning with a mass infusion of word and image driven by publishing technologies and institutions.

Timothy is currently completing a PhD in Art History at the University of British Columbia.