H4. Expanding the Frame: Uncovering and Reweaving Late Modern and Early Postmodern Canadian Fibre Arts, Wall Hangings, and Architectural Textiles

Sat Oct 21 / 15:30 – 17:15 / KC 203

chairs /

- Michele Hardy, Nickle Galleries, University of Calgary

- Julia Krueger, Independent

Elissa Auther asserts fibre was central to artistic practice in the 1960s and 1970s, and Glenn Adamson contends fibre is “an articulation of its own boundedness.” In co-curating Prairie Interlace: Weaving, Modernisms and the Expanded Frame, we explored notions of centrality, boundedness and framing while studying this period of fibre-related energy and collective creativity on the Canadian Prairies. This session seeks to further this work by inviting submissions that uncover; centralize or decentralize; weave, reweave and/or expand the frame of late modern and early postmodern Canadian fibre arts. Topics of interest include fibre arts histories; textile archives and collections; architectural textiles; domestic textile practices; textile-related theories and discourses; and challenges surrounding exhibiting, collecting, and textile care.

keywords: craft, fibre arts, textiles, weaving

session type: panel

Michele A. Hardy is a Curator with Nickle Galleries and Series Editor for Art in Profile: Canadian Art and Architecture with the University of Calgary Press. Hardy studied textiles and craft (BFA; MA) before earning a PhD in Cultural Anthropology. Her ongoing ethnographic research examines the changes affecting rural Muslim craftspeople in India as well as shifting craft traditions across Asia. Hardy’s teaching and curatorial work seek to interrogate museums’ contemporary relevance and forge new creative connections between collections and community.

Julia Krueger studied art history (BA) and Canadian art history (MA) at Carleton University in Ottawa, ON. She completed a BFA in ceramics at the Alberta College of Art + Design (ACAD) in Calgary, AB and a Ph.D. in visual culture at the University of Western Ontario in London, ON. Her research interests involve developing object inspired approaches for studying late modern (1950–1980) Canadian prairie fine craft grounded in material culture and craft theory. In addition to her studies, Julia has maintained an active writing, curatorial and research practice.

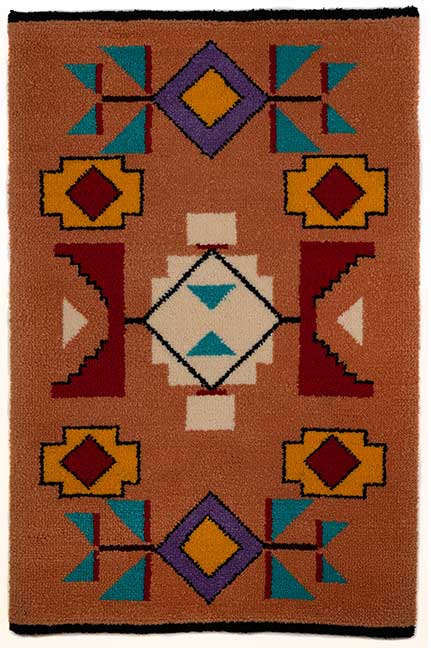

Evelyn Goodtrack, Dakota Rug, c. 1968, latch hooked; wool, cotton, 174.5 x 113.5 cm. SK Arts Permanent Collection, N70.3, Image: Dave Brown, LCR PhotoServices.

We Always Took What They Discarded: Metis Rug Hooking 1880-2020

- Bailey Randell-Monsebroten, University of Regina

Study of the Metis people’s artistic achievements has been a growing field in recent years. Much attention has been paid to their beadwork, and to a lesser extent, silk embroidery work. While this is excellent progress for the inclusion of the Metis in the Canadian Art History cannon, a lesser-known Metis art form, rug hooking, has not been as well represented.

This presentation will examine hooked rugs produced within Metis families and communities within what is now known as Saskatchewan, focusing heavily in on the works of the Pelletier/Racette family from the Qu’Appelle Valley. It will also show evidence of rug hooking existing as continuous practice for over a century, existing as a central economic driver for road allowance families through the reservation era, and discuss the current practice of rug hooking among Metis artists.

keywords: Indigenous art, textile art, Metis

Bailey Randell-Monsebroten (she/her) is a Metis Art Historian, Beader, Auntie and Graduate Student. Her family roots are in the Red River Settlement with some family names including Hodgson, Cook, McLennan, and Inkster. She originally hails from Treaty Six territory, and is currently living on Treaty Four territory. Bailey holds a Bachelor of Arts in Indigenous Studies from The First Nation’s University of Canada and is currently working on a Master of Arts in Art History and Indigenous Studies from The University of Regina.

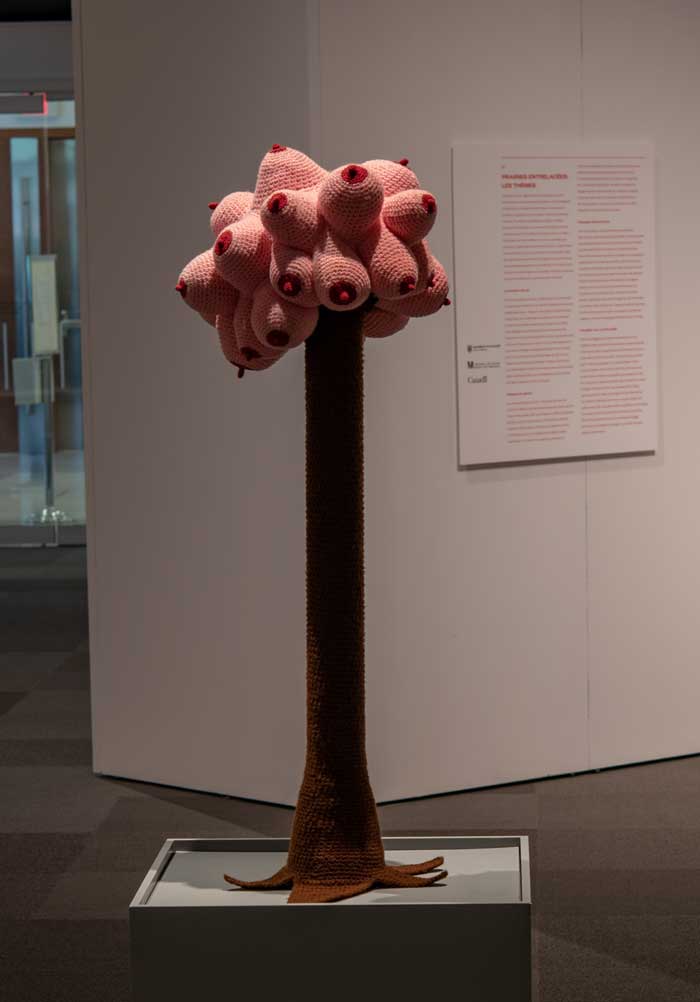

Phyllis Green, Boob Tree, 1975, crochet; yarn, wood, 109.2 x 55.9 x 50.8 cm. Collection of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Acquired with funds from the Estate of Mr. and Mrs. Bernard Naylor, funds administered by The Winnipeg Foundation, 2014-128. Image: Dave Brown, LCR PhotoServices.

Ann Newdigate, A 1988 preparatory drawing for Then there was Mrs. Rorschach's dream/You are what you see. Source: SK Arts Permanent Collection, 2000-004. Image courtesy SK Arts.

Ann Newdigate, Then there was Mrs. Rorschach's dream/You are what you see, 1988, tapestry; linen, silk, cotton, synthetic fibres, wool, cotton, 181 x 87 cm. Collection of the Canada Council Art Bank/Collection de la Banque d'art du Conseil des arts du Canada, 90/1-0261. Image: Dave Brown, LCR PhotoServices.

Contextual Bodies: From the Cradle to the Barricade

- Mireille Perron, Alberta University of the Arts

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed a vast expansion of Feminist and Craft practice, theory, criticism, and curatorial methods. While many artists in Prairie Interlace: Weaving, Modernisms and the Expanded Frame, identify/ied as textile or fibre artists, and as feminists, not all do/did. These divergences reflect a textile and/or feminist identity navigating an artistic and social space where the very notion of identity was being questioned. These works are/were a material manifestation for a desire for connections, smooth or snagged. They took up modernist key gestures such as truth to materials and abstraction, and intertwined activist, affective, poetic, and aesthetics purposes to suggest how textile can been used to advance a political agenda as well as to make material engagement synonymous with community participation. In every act of making there is an expectation for meaning, but it is rarely an explanation or a proposition. At best, it is an insinuation that opens up a space for complicity, contrast, equivalence, confirmation or conflict. These textile works invented new interpretative devices to foretell other ways to tell stories, lives, subjectivities and bodies from the cradle to the barricade.

keywords: Prairie textiles, expansion of Modernist key gestures, feminist subjectivities

Mireille Perron is an artist, writer, educator, and founder of the Laboratory of Feminist Pataphysics, promoting social experiments masquerading as artworks and events. She is Professor Emerita at Alberta University of the Arts, where, among other subjects, she taught Craft Theory. She lives and works in Calgary, Canada.

“When the Touchless Frame Meets the Frame of Touch”: Expanding the Frame of Textile Art

- Timothy Long, MacKenzie Art Gallery & University of Regina

In co-curating the MacKenzie Art Gallery/Nickle Galleries exhibition Prairie Interlace: Weaving, Modernisms, and the Expanded Frame, I have been struck by the independence of weaving and other textile artforms from the conventional frame of Western art. Framing as a physical device seems an unnecessary addition for objects which carry their own means of internal support. But more than that, it became apparent to me that the hard edge of the frame represents a foreign energy for objects whose edges were softly looped or knotted. In this paper, I propose that textile art carries its own independent frame, even while operating within the frame of Western art. If the frame of art may be defined as a parergon or “the work beside,” as proposed by Jacques Derrida in The Truth in Painting, then I would counter that the frame of weaving is defined by a synergon. or “the work together.” In making this proposal, my aim is to expand on Glenn Adamson’s conceptualization of craft as a supplement of art, a multi-faceted parergon encompassing weaving, woodworking, ceramics, glass, etc. While this is a useful construct, it would seem incomplete, for the specific energy of textiles derives from its relationship to its own supplement: the binding, knotting, interweaving, and looping which transforms individual threads into textile. Following the cultural anthropology of René Girard, I will show how both frames are ultimately located in the sacred. While art invokes the sacrificial victim through the phantom limb of aesthetic presence, weaving carries the potential to touch and clothe that limb. When weaving becomes art, the touchless frame meets the frame of touch. This ability to touch defines the expanded frame of weaving, a frame that allows for contacts to extend along the many deterministic threads upon which society hangs—the “bad habits of the West,” as tapestry artist Ann Newdigate has so trenchantly called them.

keywords: textile art, framing, Glenn Adamson, René Girard, parergon

Timothy Long has over thirty years of curatorial experience at the MacKenzie Art Gallery where he is Head Curator and Adjunct Professor at the University of Regina. Writing regional art histories and assessing their impacts has driven several of his collaborative investigations, including Regina Clay: Worlds in the Making, Superscreen: The Making of an Artist-Run Counterculture and the Grand Western Canadian Screen Shop (with Alex King), and retrospectives of Marilyn Levine, Jack Sures, David Thauberger (with Sandra Fraser), and Victor Cicansky (with Julia Krueger). Other projects, including Atom Egoyan: Steenbeckett (with Christine Ramsay and Elizabeth Matheson) and the MAGDANCE series of exhibition/dance residencies with New Dance Horizons, are the result of his interest in interdisciplinary dialogues between art, sound, ceramics, film, and contemporary dance. In 2022, Long addressed the critical potential of weaving in Prairie Interlace: Weaving, Modernisms, and the Expanded Frame, co-curated with Julia Krueger and Michelle Hardy.

Prairie Interlace: Weaving, Modernisms and the Expanded Frame (installation view, Nickle Galleries, with Ta-hah-sheena rugs in the background). Image: Dave Brown, LCR PhotoServices.

Tah-Hah-Sheena: a Dakota Arts Co-operative on the Prairies, 1968-1974

- Sherry Farrell Racette, University of Regina

Ta-hah-sheena was a rug-making co-operative on Standing Buffalo First Nation that merged the bold graphics of Dakota narrative symbology with latch-hook wool rug-making techniques. The co-operative originated from a two-week class organized by Lorna Bell Ferguson, the wife of a local teacher. However, it was female elders, led by Martha Tawiyaka, who were the creative engine of the project. At its peak, the co-operative had forty-eight members ranging in age from eighteen to ninety-two. Although it was based on the co-operative model popular at the time, the underlying structure was the Dakota tióšpaye, the complex network of extended families centered around women. Artists were often sisters, aunties, cousins, and sisters-in-law. These relationships enhance the elder advisors’ capacity and comfort in transferring knowledge to younger members.

The co-operative emerged at a time when each level of government viewed Indigenous creativity as an untapped natural resource that, if properly managed, could address economic hardships. Having committed to Inuit co-operatives, the federal government embraced “Eskimo Art” and was tentatively moving towards the idea of First Nations men as professional artists, but women were generally tethered to craft production for a low-end tourist market. With its bold, often large-scale woven rugs, Ta-hah-sheena hovered between categories. Despite international marketing efforts, the co-operative never found its place. However, the dynamic aesthetics of the surviving rugs, the pride associated with the co operative, and the persistence of rug-making among Standing Buffalo artists suggests the potential for return.

keywords: Dakota, textiles, rug-making, co-operative

Sherry Farrell Racette is an interdisciplinary scholar with an active artistic and curatorial practice. Her work is grounded in extensive work in archives and museum collections with an emphasis on Indigenous women and recovering aesthetic knowledge. Beadwork and stitch-based work is important to her artistic practice, creative research, and pedagogy. In 2016 Farrell Racette was the Distinguished Visiting Indigenous Faculty Fellow, at the Jackman Humanities Institute, University of Toronto and in 2021 received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the University Art Association of Canada (UAAC-AAUC). She was born in Manitoba and is a member of Timiskaming First Nation in Quebec.